Alain Brassard, MD, FRCPC; Richard Langley, MD, FRCP(C); and Yves Poulin, MD, FRCPC

Alain Brassard, MD, FRCPC

Professor,

Division of Dermatology and Cutaneous Sciences,

University of Alberta

Richard Langley, MD, FRCP(C)

Professor of Dermatology,

Director of Research,

Division of Dermatology,

Department of Medicine,

Dalhousie University

Yves Poulin, MD, FRCPC

Associate Clinical Professor,

Division of Dermatology,

Department of Medicine,

Laval University

Hôpital Hôtel-Dieu de Québec

President,

Center for Research in Dermatology of Quebec

Introduction

Systemic biologic therapies are integral components of the treatment armamentarium for moderate-to-severe psoriasis.1 Anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents and the interleukin (IL)-12/23 inhibitor ustekinumab are well-established agents and, in the past two years, two additional important agents have been added to the list, with inhibitors of IL-17 (ixekizumab and secukinumab) approved for use in Canada.2 Another inhibitor of IL-17, brodalumab, was approved recently in the United States (U.S.) and is expected to be approved in Canada in the near future.

The Annual Scientific Meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) is one of the most important conferences at which new research with existing and emerging agents is presented. This year’s event, held in Orlando, Florida, from March 3 to 7, continued to show that the next wave of potent biologics to become available for moderate-to-severe psoriasis will be the anti-IL-23 biologics (e.g., guselkumab, tildrakizumab and risankizumab).

This report provides a summary of the key highlights of new research with the IL-23 inhibitors presented at AAD 2017. It also summarizes research that adds to our understanding of the efficacy, safety and clinical use of already-approved biologic agents.

New Research with Anti-IL-23 Agents

GUSELKUMAB. The primary results of one of the pivotal guselkumab studies, VOYAGE-1, were presented at the scientific meeting of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) in the fall of 2016.3 The primary results of two other pivotal trials, VOYAGE-2 and NAVIGATE, were presented at AAD 2017.4,5 Additionally, both VOYAGE-1 and -2 were published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology in the March 2017 issue.6,7

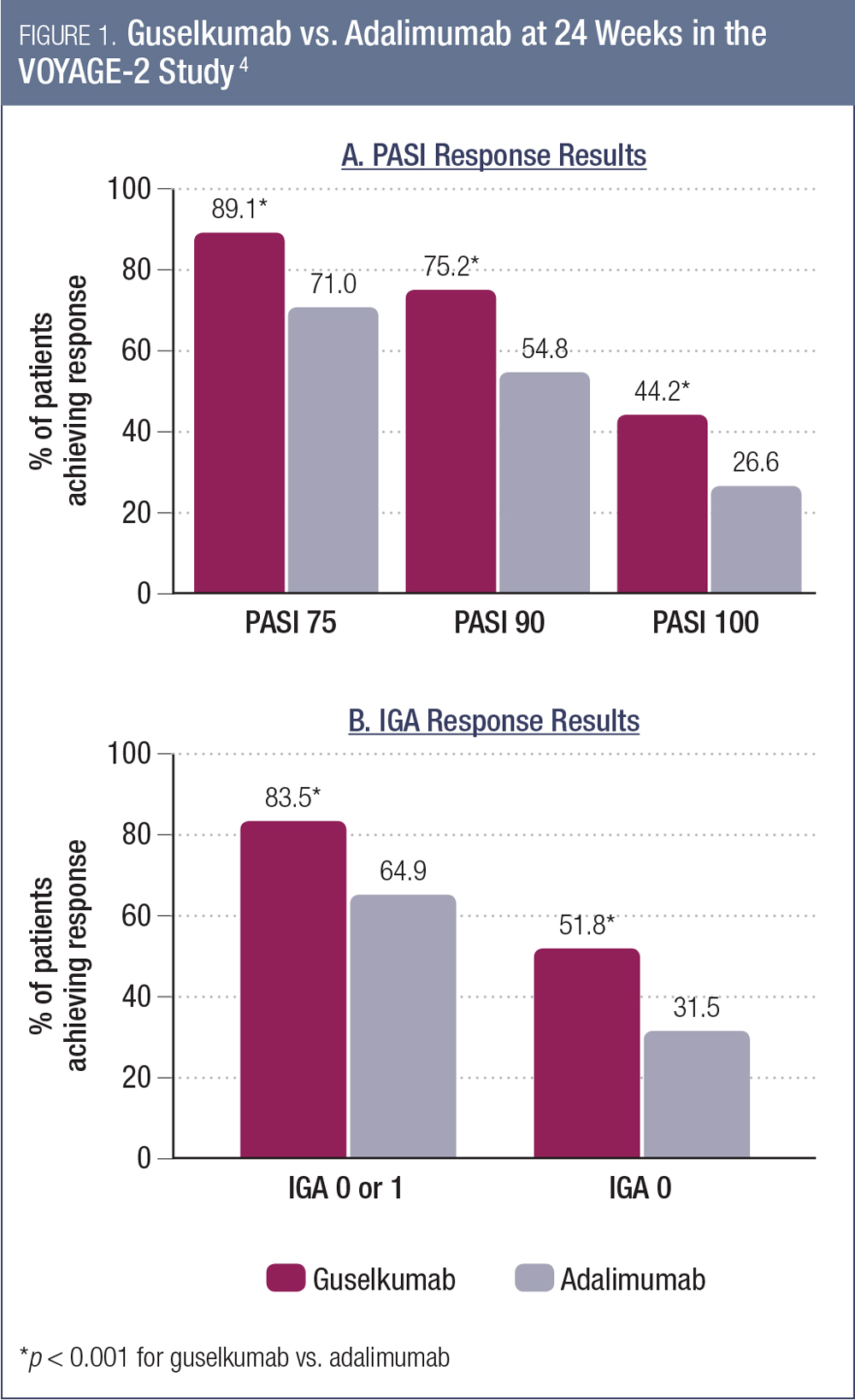

In VOYAGE-2, patients were randomized to receive guselkumab 100 mg at weeks 0, 4, 12, and 20, or placebo at weeks 0, 4, and 12, followed by guselkumab 100 mg at weeks 16 and 20, or adalimumab 80 mg at week 0, 40 mg at week 1, then 40 mg every two weeks through week 23.4 The co-primary endpoints were the proportion of guselkumab vs. placebo patients achieving ≥ 90% improvement in the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index score (PASI 90) and an Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) score of cleared (0) or minimal disease (1) at week 16. The key secondary endpoints were efficacy assessments of guselkumab vs. adalimumab at week 24.

As was the case in VOYAGE-1, guselkumab was found to be superior to placebo for both primary endpoints. The proportions of patients achieving PASI 90 and IGA 0-1 with guselkumab at week 16 were 84.1% and 70.0% (compared to 8.5% and 2.4% for placebo, p < 0.001 for both comparisons).4 The proportions of patients achieving PASI 75, PASI 90 and PASI 100 at week 24 were all significantly greater for guselkumab compared to adalimumab (Figure 1a).4 Between-group differences for each of these endpoints also were statistically significant at week 16. Similarly, the IGA responses were superior for guselkumab vs. adalimumab at week 24 (Figure 1b).4 As was the case in VOYAGE-1, guselkumab was well tolerated, with an adverse event profile similar to adalimumab.4 The VOYAGE-2 study also included a randomized withdrawal and re-treatment period.7 Among those patients who achieved a PASI 90 response and were then randomized to treatment withdrawal, there was a persistent treatment effect of guselkumab. The median time to loss of PASI 90 response was 15.2 weeks.7

Also at AAD 2017, additional data were presented from the VOYAGE-1 and -2 studies. One of the analyses showed the consistency of response to guselkumab across predetermined subgroups, using data from both studies;8 another showed superiority of guselkumab vs. adalimumab for scalp, nail and hands/feet in the VOYAGE-1 trial;9 a similar analysis of VOYAGE-2 data validated the scalp and hands/feet results, but the difference in the nail findings was not statistically significant.10

One of the other data sets presented at AAD 2017 were the patient-reported outcomes (PROs) for guselkumab vs. adalimumab in the VOYAGE-1 study.11 These were evaluated using the Psoriasis Symptoms and Signs Diary (PSSD), a self-administered, validated tool for psoriasis symptoms and signs. Patients treated with guselkumab had greater self-reported improvements in both symptoms and signs of psoriasis as measured by the PSSD. The proportions of patients achieving a clinically meaningful improvement in the symptoms score at week 48 were 81.0% with guselkumab and 60.1% with adalimumab (p < 0.001).11 For the signs score, the proportions were 82.2% and 63.3% for guselkumab and adalimumab, respectively (p < 0.001).11

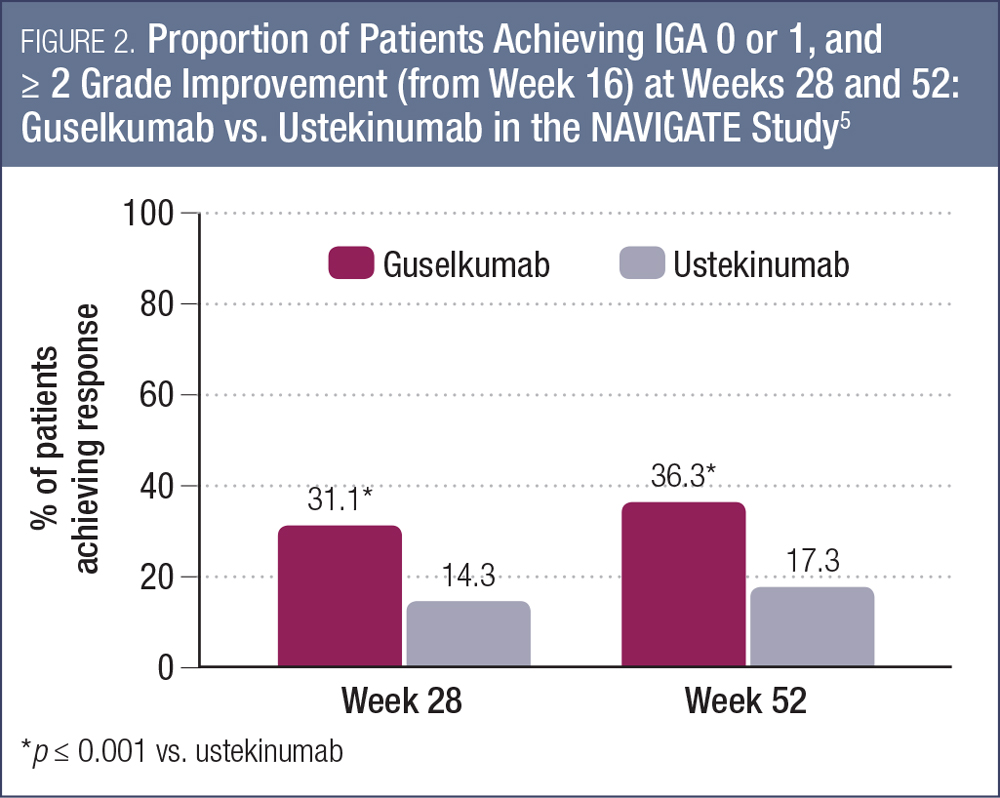

Another key study demonstrating the utility of guselkumab for patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis is the NAVIGATE study, which evaluated the efficacy of switching from ustekinumab to guselkumab in nonresponders.5, 12 In this study, 871 patients initially received open-label ustekinumab (45 or 90 mg based on weight) at weeks 0 and 4. At week 16, those individuals who had an IGA score of 2 or higher (n = 268) were randomized to continue ustekinumab therapy (at weeks 16, 28 and 40, n = 133) or switch to guselkumab 100 mg at weeks 16, 20, 28, 36 and 44 (n = 135). The primary endpoint was the number of visits from week 28 to week 40 with IGA 0 or 1 and ≥ 2-grade improvement from week 16.5

For the primary endpoint, the mean number of visits meeting these criteria were 1.5 for guselkumab and 0.7 for ustekinumab (p < 0.001).5 As shown in Figure 2, the proportions of patients achieving this endpoint at weeks 28 and 52 were significantly higher for those switched to guselkumab compared to those who continued on ustekinumab (p < 0.001 for both time points). By week 52, 36.3% of patients had reached the endpoint with guselkumab compared with 17.3% who continued with ustekinumab.5

PASI 90 was achieved by 48.1% and 51.1% of guselkumab patients at weeks 28 and 52, compared with 22.6% and 24.1% of those who continued ustekinumab therapy. Switching to guselkumab was well tolerated in this study.5 The safety profile of guselkumab was also favorable and similar to ustekinumab. For example, with respect to major adverse cardiovascular effects, there were two events among those switched to guselkumab (1.5%) and one event among those continuing on ustekinumab (0.8%).5

With respect to PROs, severity of symptoms and observable signs were assessed using the PSSD. Health-related quality of life was assessed with the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI).12 The proportions of patients who reported a PSSD symptoms score of 0 at week 52 was 20.3% with guselkumab and 9.5% for ustekinumab (p = 0.017).12 For PSSD signs, 9.0% of guselkumab patients reported a score of 0, compared to 3.1% with ustekinumab (p = 0.045). Guselkumab also was found to be superior with respect to DLQI score at week 52; 38.8% of those switched to guselkumab achieved a DLQI of 0 or 1, compared to 19.0% with continued ustekinumab.12

Guselkumab also has been evaluated for the treatment of other psoriasis variants. An open-label, single-arm phase 3 study conducted in Japan and presented at AAD 2017 showed that seven of nine patients with generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP) and ten of 11 patients with erythrodermic psoriasis (EP) experienced treatment success (“very much improved,”“much improved,” or “minimally improved” based on Clinical Global Impression [CGI] assessment) with guselkumab.13

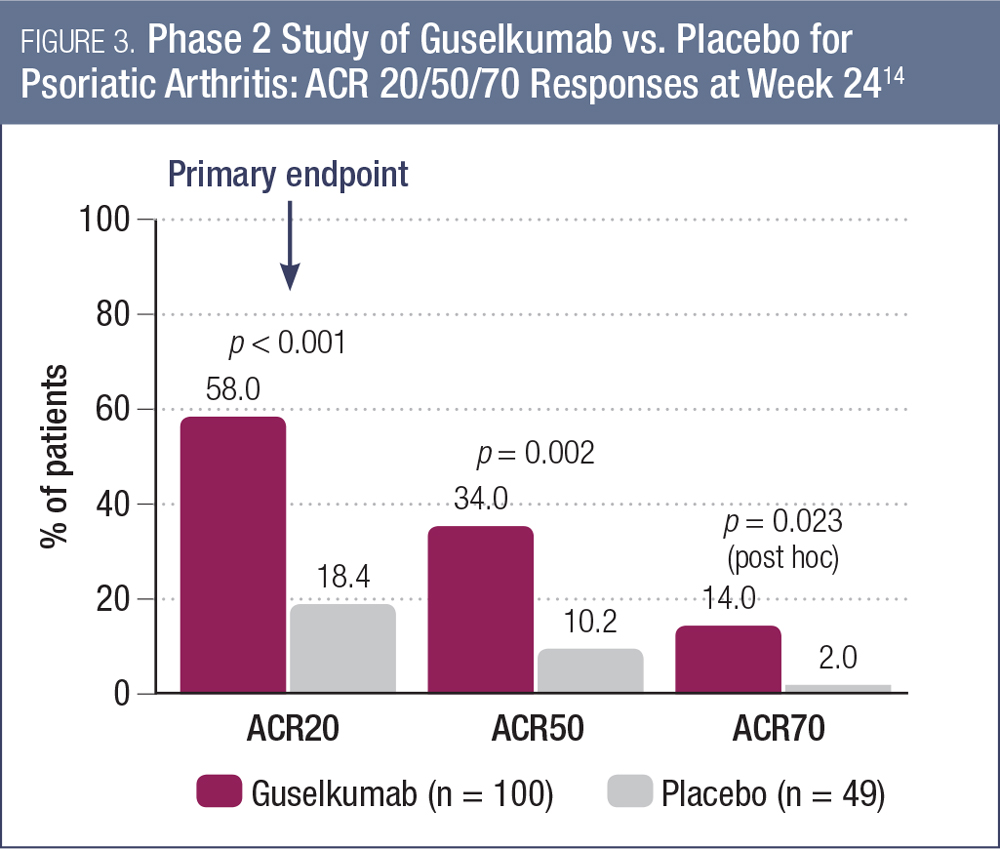

Finally, guselkumab also was evaluated among patients with active psoriatic arthritis (PsA) and plaque psoriasis with at least 3% body surface area in a phase 2 study.14 The study was placebo-controlled for the first 24 weeks. The results, presented at AAD 2017, showed that guselkumab was superior to placebo for the primary endpoint of a 20% improvement in the American College of Rheumatology (ACR20) response at week 24 (58.0% vs. 18.4%, p < 0.001; Figure 3).14

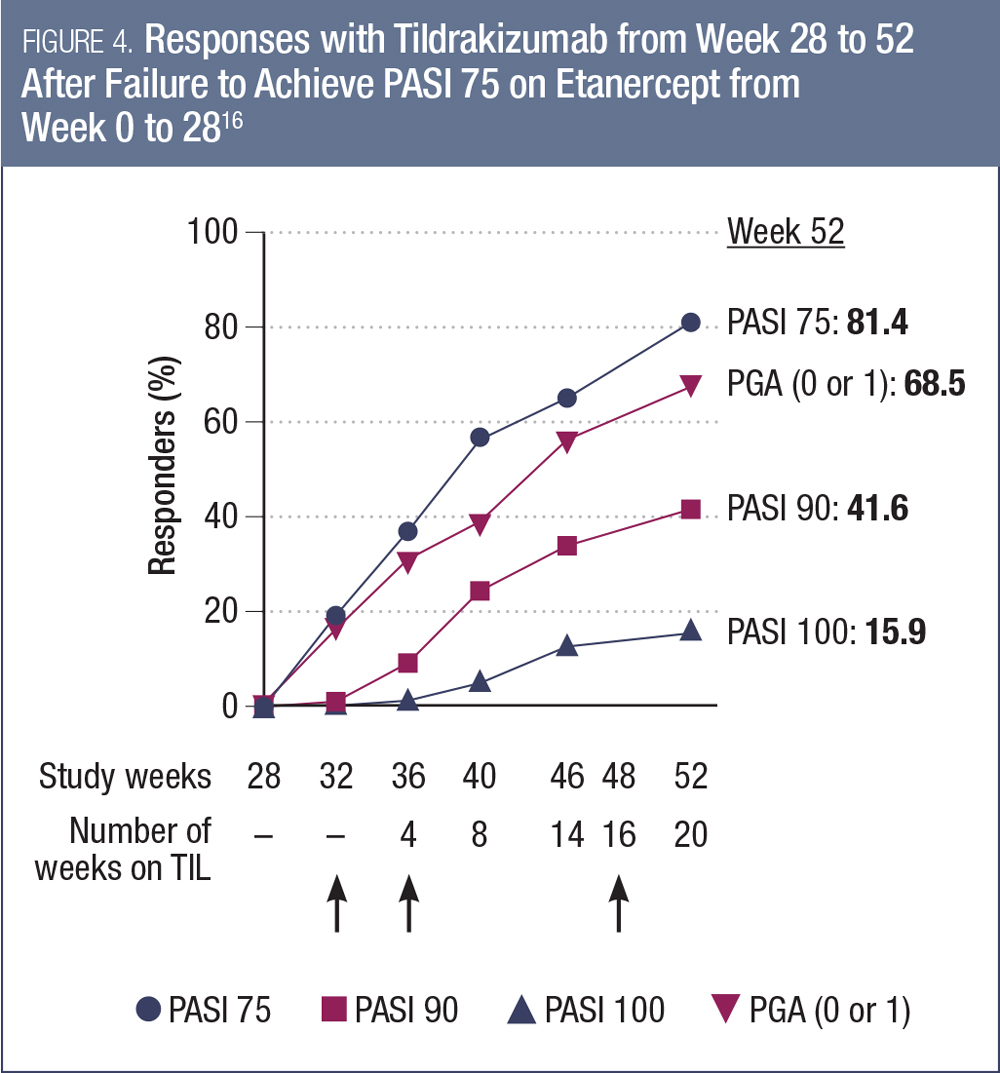

TILDRAKIZUMAB. There also was data presented at AAD 2017 from studies investigating another anti-IL-23 agent, tildrakizumab. Pivotal trial results from the reSURFACE-1 and -2 trials had previously been presented at the EADV 2016 annual meeting, with efficacy and safety data to week 28.15 At AAD 2017, researchers presented an analysis of the reSURFACE-2 study examining the subset of patients who had not responded to the active control etanercept over the initial 28 weeks of the study.16 Of the 313 patients randomized to initial etanercept, 120 did not achieve PASI 75 by week 28. Among these patients, a substantial proportion responded to tildrakizumab in the 36 weeks following the switch (Figure 4).16

Additionally, researchers showed that among patients in RESURFACE-1 and -2, more than half the patients who were subsequently randomized to treatment discontinuation experienced a relapse (reduction in maximum PASI response by 50%). Most of these patients (approximately 85%) were able to recapture a PASI 75 response with tildrakizumab retreatment.17 Among those who continued on tildrakizumab after week 28, PASI 75 was maintained in 89-94% of patients, depending on the dose.

RISANKIZUMAB. Although there was no new research with this agent presented at AAD 2017, risankizumab was mentioned in several overview presentations. It has previously demonstrated favorable results relative to ustekinumab in a head-to-head phase 2 study18 and is now being investigated in phase 3 studies.

New Research with Anti-IL-17 Agents

IXEKIZUMAB. Although ixekizumab already has been approved for use in Canada on the basis of its clinical trial program, additional data continue to accumulate.

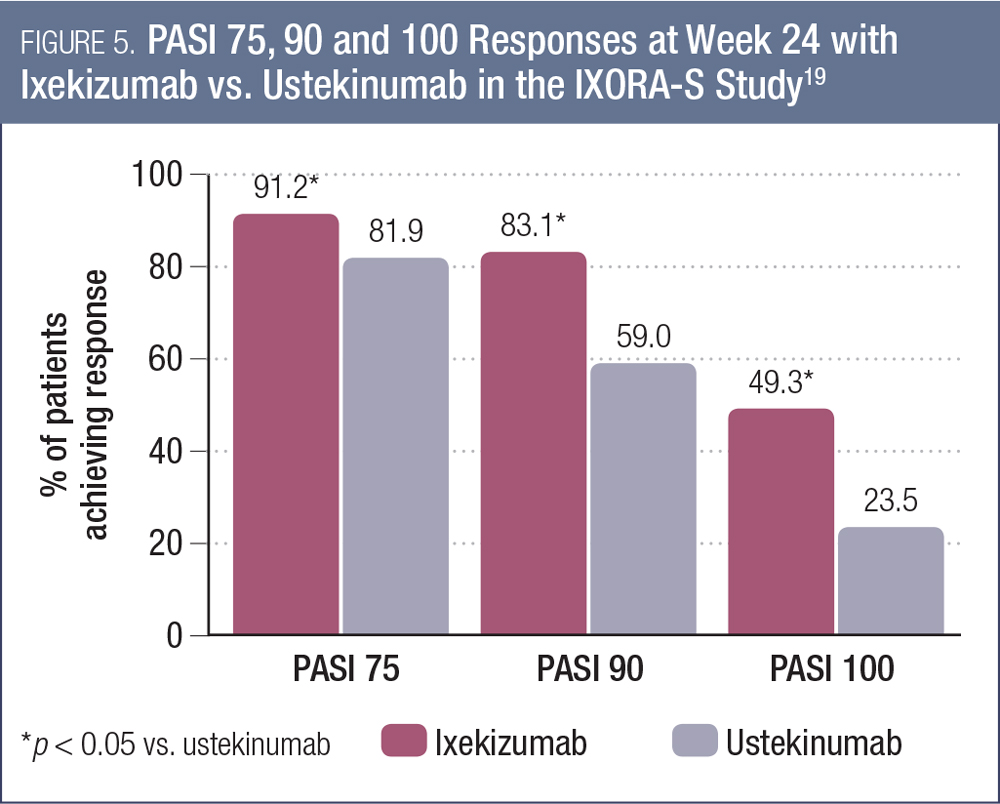

The most noteworthy data presented at AAD 2017 for this agent were the 24-week results of the IXORA-S study, comparing ixekizumab to ustekinumab in 302 patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis.19 Ixekizumab was administered with a 160 mg starting dose at week 0, followed by 80 mg every two weeks through week 12 and 80 mg every four weeks thereafter (n = 136). Ustekinumab was administered (45 mg or 90 mg by weight) at weeks 0, 4 and 16.

As shown in Figure 5, the PASI response rates were significantly higher with ixekizumab compared to ustekinumab at week 24 (each comparison p < 0.001).19 The proportion of patients achieving a DLQI score of 0 or 1 also was significantly higher with ixekizumab (66.2% vs. 53.0%, p < 0.05). There were no significant between-group differences in overall rates of adverse events. This study is ongoing, with follow-up to continue to week 64.

Other research presented at AAD 2017 with ixekizumab included pooled analyses of the pivotal trials UNCOVER-1, -2 and -3 showing superior efficacy of ixekizumab vs. etanercept and placebo for specific body regions (e.g., head, trunk, arms and legs);20 consistent efficacy of ixekizumab compared to placebo and etanercept across baseline subgroups;21 and maintenance of efficacy out to week 108 (in the UNCOVER-3 study).22

Additionally, long-term (four-year) data were presented from an open-label extension of a phase 2 study (n = 120).23 In this analysis, the investigators noted that ixekizumab was associated with sustained improvements in nail psoriasis, scalp psoriasis, health-related quality of life, itch and disease activity.23 In the same study, among the 38 patients with psoriatic arthritis enrolled in the long-term extension, sustained improvements were noted in PASI scores, static Physician Global Assessment [sPGA] and the psoriatic arthritis pain Visual Analog Scale.24

Several groups also presented reassuring safety results with ixekizumab, including: a pooled analysis of seven clinical trials showing no activation of tuberculosis;25 an analysis of the UNCOVER studies showing a neutral metabolic profile;26 a study in healthy male volunteers showing no impact of ixekizumab on effectiveness of the tetanus (Boostrix) and pneumococcal (Pneumovax 23) vaccines;27 and initial data on pregnancies (n = 34) showing no evidence of congenital abnormalities.28

SECUKINUMAB. A wealth of new data were presented for this anti-IL-17 agent as well. Much of the new information came from sub-group and post-hoc analyses of the CLEAR study, the pivotal head-to-head trial vs. ustekinumab in moderate-to-severe psoriasis. This included long-term (52-week) benefits in skin clearance, quality of life and patient-reported outcomes.29-35

Additionally, separate study reports demonstrated benefit of secukinumab on patient-reported outcomes for scalp psoriasis at 12 weeks;36 long-term benefit on nail psoriasis over 1.5 years (from the TRANSFIGURE phase 3b study);37 sustained improvements in quality of life over three years (from the SCULPTURE extension study);38 and long-term (1.5-year) benefits on patient-reported outcomes among patients with palmoplantar psoriasis (from the GESTURE study).39

A withdrawal and retreatment analysis also was presented for secukinumab. Patients who had initially achieved PASI 75 over 52 weeks in the ERASURE and FIXTURE studies and who elected to enter the extension study were randomized to continue on the same dose of secukinumab every four weeks or to switch to placebo.40 Of the 181 patients who were switched to placebo, 136 relapsed (loss of > 50% of the maximum PASI gain compared with baseline in the core studies). The median time to relapse was 28 weeks. Retreatment with secukinumab was able to recapture PASI 75 response in 93.8% of relapsers.40

There also were several presentations of registry data/real-world outcomes with secukinumab.41-45 These included two Canadian studies that concluded that the real-world efficacy and quality of life outcomes observed were consistent with the clinical trial experience with this agent.41,42 Analysis of the CORRONA registry of individuals with psoriasis (n = 1,529 as of May 31, 2016) showed that patients taking secukinumab had characteristics indicative of more severe disease than patients taking other medications (ustekinumab, etanercept, adalimumab or non-biologics) in this registry.43,44

BRODALUMAB. This anti-IL-17 agent was recently approved in the U.S. and is undergoing regulatory review in Canada. The pivotal trials for this agent in psoriasis (AMAGINE-1, -2 and -3) have been previously presented and published.44-46 Notably, the product labeling in the U.S. includes a black box warning of a potential increased risk of suicidal ideation and behaviour (SIB).47

At AAD 2017, there were several follow-up analyses from the AMAGINE clinical trial program, including improvements in scalp and nail psoriasis;48,49 demonstration of a rapid onset of action, differentiating from ustekinumab as early as week 1,50,51 and similar efficacy of brodalumab regardless of prior biologic use.52

Importantly, researchers investigated the potential link between brodalumab and SIB, using data from the AMAGINE-1, -2 and -3 trials.53 They reported that scores for anxiety and depression were improved from baseline among patients receiving brodalumab and that rates of SIB over 52 weeks were similar with brodalumab and the active comparator, ustekinumab. They concluded that the controlled data do not suggest a causal relationship between brodalumab treatment and SIB.53 A separate analysis also concluded that there is no increased cardiovascular risk associated with brodalumab treatment.54

New Research with Anti-TNF Agents

While most of the originator anti-TNF agents have concluded their clinical trial programs, the primary results of two phase 3 studies of certolizumab pegol (CZP) in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis were presented at the 2017 AAD meeting.55 This agent, which is currently approved for psoriatic arthritis in Canada, but not plaque psoriasis, was evaluated in two identically designed phase 3 studies, CIMPASI-1 and CIMPASI-2. In the two studies, a total of 461 patients were randomized to placebo, CZP 200 mg or CZP 400 mg every two weeks. The primary endpoints were PASI 75 and Physician Global Assessment [PGA] 0/1 responder rates at 16 weeks. CZP achieved PASI 75 and PGA 0/1 response rates that were superior to placebo at the week 16 analysis. PASI 75 rates for placebo were 6.5% and 11.6% in CIMPASI-1 and -2, respectively, while those for CZP 200 mg were 66.5% and 81.4% and those for CZP 400 mg were 75.8% and 82.6% (all comparisons vs. placebo p < 0.0001).56 PGA 0/1 responses were achieved by 4.2% and 2.0% of placebo-treated subjects in CIMPASI-1 and -2, respectively, while the rates were 47.0% and 66.8% for CZP 200 mg and 57.9% and 71.6% for CZP 400 mg. There were no new tolerability or safety signals seen with CZP in these studies.

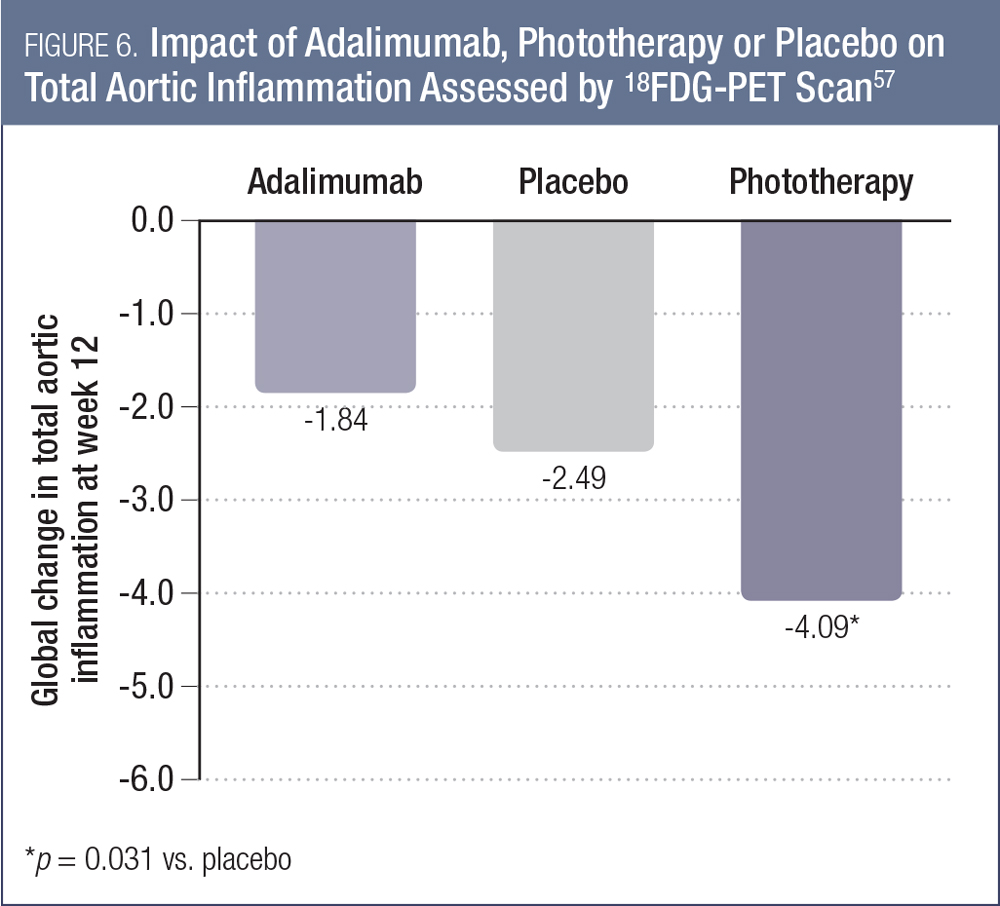

TNF INHIBITORS AND VASCULAR INFLAMMATION. A Canadian study presented by Dr. Robert Bissonnette at AAD 2017 compared the impact of treatment with the TNF inhibitor adalimumab or placebo on vascular inflammation among 107 patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis.56 Using previously validated 18fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-positron emission tomography (PET) scanning techniques, the researchers found that there was no difference in vascular inflammation over 16 weeks between adalimumab- and placebo-treated patients. In fact, there was a modest increase in carotid inflammation observed with adalimumab at 52 weeks compared to placebo.

These findings were echoed by other researchers at AAD 2017. During a plenary session at the event, Dr. Joel Gelfand presented some of the key data from the Vascular Inflammation in Psoriasis (VIP) study.57 This was a double-blind, placebo-controlled study evaluating the impact of adalimumab, phototherapy or placebo on 18FDG-PET parameters of vascular inflammation among 96 patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis. As shown in Figure 6, the global change in total aortic inflammation at week 12 was not significantly different for adalimumab vs. placebo, but was for phototherapy vs. placebo.56

Although both these studies were negative, it remains possible that a benefit of TNF-inhibitor therapy may have been seen if the trial was conducted among patients with more severe psoriasis and/or if the study was of a longer duration.57

BIOSIMILARS. Biosimilar products for products that are off-patent or soon to be off-patent have been emerging over the past several years. At the 2017 AAD, two clinical trials were presented showing non-inferior efficacy of biosimilar products in psoriasis patients. The etanercept biosimilar CHS-0214 demonstrated equivalence to the originator product for the primary endpoint of PASI 75 at week 12 (as well as for several other efficacy endpoints at weeks 12 and 48 (n = 521);58 and the adalimumab biosimilar GP2017 demonstrated equivalence to the originator product for PASI 75 at week 16, as well as several other efficacy evaluations over the 17-week study (n = 465).59

BRIEF RECAP OF KEY THEMES

Discussion by Drs. Alain Brassard, Richard Langley and Yves Poulin

There were some key themes that emerged among the many psoriasis-specific symposia at AAD 2017.

PSORIASIS AND CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE. With respect to cardiovascular (CV) morbidity among patients with psoriasis, the consistent message was that patients with psoriasis are at elevated risk of CV disease. While the evidence shows that the risk is highest among patients with severe psoriasis, even those with mild disease have an elevated risk relative to the general population. Accounting for this elevation in risk when using CV risk calculators (e.g., Framingham Risk Scores) is a work in progress. The impact of psoriasis treatments on CV risk also is a matter of some debate, with no clear consensus having emerged, and some assumptions challenged by recent data (e.g., proposed benefit of TNF inhibitors on CV risk challenged by the above findings with respect to vascular inflammation).

BIOSIMILARS. The continued emergence of biosimilars for anti-TNF therapies was the focus of several presentations at AAD 2017. Presenters discussed the regulatory requirements for these agents (chiefly in the U.S. context), the potential for cost savings and the theoretical enhanced access to biologic drugs, and outlined some of the concerns that have emerged during the debate on biosimilars in the U.S. Among these is the concern that multiple biosimilars of the same originator biologic may have proven to be equivalent to the originator, but may not be equivalent to each other, which could have an impact on patient outcomes when switching between these agents.

WHICH BIOLOGIC TO USE FIRST? While anti-TNF agents have been successfully used for more than a decade for the treatment of psoriasis, the enhanced efficacy of the newer compounds (anti-IL-23, anti-IL-17) has caused clinicians to debate the merits of preferentially using one type of agent over another as a first-line biologic. Indeed, at AAD 2017, this was formally debated by Drs. Richard Langley and Kenneth Gordon, with Dr. Langley on the side of the newer agents.60

The key points in favor of the anti-TNF agents is that they have excellent efficacy, favorable impact on key common comorbidities (e.g., psoriatic arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease) and have a well-established safety record, with millions of patients having been treated with these agents.

Working in favor of the newer agents is their unparalleled efficacy in terms of skin clearance, with PASI 90 responses expected in more than 80% of patients treated with these agents, and full clearance a possibility for a substantial minority of patients. Research to date also has suggested that these agents have a safety profile similar to that of the anti-TNF agents, with no major safety concerns having emerged (with the exception of the SIB concern with brodalumab).

Regardless of the treatment chosen, the accumulation of research and clinical experience with biologics in psoriasis, amply augmented by the work presented at AAD 2017, provides clinicians and patients alike with a wealth of evidence-based, efficacious and safe choices for the treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis.

References:

1. Canadian Psoriasis Guidelines Committee. Canadian Guidelines for the Management of Plaque Psoriasis, June 2009. http://www.dermatology.ca/psoriasisguidelines.

2. Health Canada. Notice of Compliance On-line Database. https://health-products.canada.ca/noc-ac/index-eng.jsp; Accessed March 2017.

3. Blauvelt A, et al. Level of efficacy and safety of guselkumab, an anti-interleukin-23 monoclonal antibody, compared with adalimumab for the continuous treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis in the phase 3 VOYAGE 1 trial. Presented at EADV 2016; Presentation #D3T01.1D.

4. Reich K, Armstrong AW, Foley P, et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab compared with adalimumab for the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis: results from the phase 3, double-blind, placebo- and active comparator-controlled VOYAGE-2 trial. Presented at AAD 2017; Poster #P4749.

5. Langley RG, Tsai T-F, Flavin S, et al. Efficacy of switching from ustekinumab to guselkumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: results from the NAVIGATE Study. Presented at AAD 2017; Poster #P4749.

6. Blauvelt A, Papp KA, Griffiths CE, et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab, an anti-interleukin-23 monoclonal antibody, compared with adalimumab for the continuous treatment of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis: Results from the phase III, double-blinded, placebo- and active comparator-controlled VOYAGE-1 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017; 76(3):405-17.

7. Reich K, Armstrong AW, Foley P, et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab, an anti-interleukin-23 monoclonal antibody, compared with adalimumab for the treatment of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis with randomized withdrawal and retreatment: Results from the phase III, double-blind, placebo- and active comparator-controlled VOYAGE-2 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017; 76(3):418-31.

8. Blauvelt A, Reich K, Papp K, et al. Consistency of response across subgroups of patients with psoriasis treated with guselkumab: results from the VOYAGE-1 and -2 Trials. Presented at AAD 2017; Poster #P4895.

9. Blauvelt A, Papp K, Griffiths CE, et al. Efficacy of guselkumab within specific body regions in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: results from the phase 3 VOYAGE-1 Study. Presented at AAD 2017; Poster #P4768.

10. Reich K, Armstrong AW, Foley P, et al. Efficacy of guselkumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis with involvement of the scalp, nails, hands, and feet: results from the phase 3 VOYAGE-2 Study. Presented at AAD 2017; Poster #P4827.

11. Blauvelt A, Papp K, Griffiths CE, et al. Patient-reported symptoms and signs in patients with moderate-severe plaque psoriasis treated with guselkumab or adalimumab: results from VOYAGE-1, a phase III clinical trial. Presented at AAD 2017; Poster #P4766.

12. Langley RG, Tsai T-F, Han C, et al. Guselkumab therapy improves patient-reported signs, symptoms and health-related quality of life of patients with moderate- severe psoriasis with inadequate response to ustekinumab: results from phase III NAVIGATE Study. Presented at AAD 2017; Poster #P917.

13. Morishima H, Goto R, Zheng R, et al. Phase 3 study of guselkumab, a human mAb directed against the p19 subunit of IL23, in Japanese subjects with generalized pustular psoriasis and erythrodermic psoriasis. Presented at AAD 2017; Poster #P4526.

14. Gottlieb A, Deodhar A, Boehncke W-H, et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab, an anti-IL23 monoclonal antibody, in patients with active psoriatic arthritis: a phase 2a, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Presented at AAD 2017; Poster #P4454.

15. Reich K, Papp K, Blauvelt A, et al. Tildrakizumab, a selective IL-23p19 antibody, in the treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis: results from two randomized, controlled, phase 3 trials (reSURFACE 1 and reSURFACE 2). Presented at EADV 2016; Presentation #D3T01.1I.

16. Reich K, Papp K, Blauvelt A, et al. Tildrakizumab, a selective anti-IL-23 monoclonal antibody, is effective in subjects with chronic plaque psoriasis who do not adequately respond to etanercept. Presented at AAD 2017; Poster #P5252.

17. Papp K; Kimball AB; Tyring S, et al. Maintenance of treatment response in chronic plaque psoriasis patients continuing treatment or discontinuing treatment with tildrakizumab in a 64-week, randomized controlled, phase 3 trial. Presented at AAD 2017; Poster #P4855.

18. Papp K, et al. Onset and duration of clinical response following treatment with a selective IL-23p19 inhibitor (BI 655066) compared with ustekinumab in patients with moderate-to-severe chronic plaque psoriasis. Presented at EADV 2015; abstract #FC03.06.

19. Reich K, Lacour JP, Dutronc Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of ixekizumab compared to ustekinumab after 24 weeks of treatment in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: Results from IXORA-S, a randomized head-to-head trial. Presented at AAD 2017; Presentation #5078.

20. Blauvelt A, Muram T, See K, et al. Clearing of psoriasis within different body regions following 12 weeks of treatment with ixekizumab. Presented at AAD 2017; Poster #P4551.

21. Pariser D, Heffernan M, Dennehy EB, et al. The effects of age, gender, weight, age at onset, psoriasis severity, nail involvement, and presence of psoriatic arthritis at baseline on the efficacy of ixekizumab in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis. Presented at AAD 2017; Poster #P4622.

22. Blauvelt A, Gooderham M, Iversen L, et al. Efficacy and safety of ixekizumab for the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: results through 108 weeks of a randomized, phase III clinical trial (UNCOVER-3). Presented at AAD 2017; Poster #P4376.

23. Kimball AB, Zachariae C, Burge R, et al. The effect of ixekizumab on scalp and nail psoriasis and health outcome measures over four years of open-label treatment in a phase 2 study in chronic plaque psoriasis. Presented at AAD 2017; Poster #P4530.

24. Lebwohl M, Adams D, McKean-Matthews M, et al. Ixekizumab efficacy in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis and co-morbid psoriatic arthritis: four year results from a phase 2 study. Presented at AAD 2017; Poster #P4629.

25. Romiti R, Valenzuela F, Chouela EN, et al. Ixekizumab treatment shows no evidence for reactivation of previous or latent tuberculosis infection in patients with psoriasis: an integrated analysis of 7 clinical trials. Presented at AAD 2017; Poster #P4550.

26. Wu JJ, Egeberg A, Solomon JA, et al. Ixekizumab treatment shows a neutral impact on the glucose and lipid profile of patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis: results from UNCOVER-1, -2, and -3. Presented at AAD 2017; Poster #P4662.

27. Gomez EV, Bishop JL, Jackson K, et al. Treatment with ixekizumab does not interfere with the efficacy of tetanus and pneumococcal vaccines in healthy subjects. Presented at AAD 2017; Poster #P5105.

28. Feldman SR, Pangallo B, Xu W, et al. Ixekizumab and pregnancy outcome. Presented at AAD 2017; Poster #P4532.

29. Strober B, Jazayeri S, Thaçi D, et al. Secukinumab provides faster and more sustained 52-week complete relief from psoriasis-related pain, itching, and scaling than ustekinumab in subjects with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Presented at AAD 2017; Poster #4449.

30. Secukinumab Provides greater 52-week improvements in patient-reported outcomes than ustekinumab in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. Presented at AAD 2017; Poster #4797.

31. Vender R, Leonardi C, Puig L, et al. Secukinumab provides greater cumulative 52-week skin clearance and quality of life benefit in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis than ustekinumab: an area-under-the-curve analysis. Presented at AAD 2017; Poster #4798.

32. Blauvelt A, Mehlis S, Vanaclocha F, et al. Secukinumab provides greater 52-week sustained relief from dermatology-related quality of life impact on clothing choice and sexual function than ustekinumab. Presented at AAD 2017; Poster #4799.

33. Gottlieb AB, Pariser D, Tsai T-F, et al. Secukinumab provides greater 52-week sustained relief in dermatology-specific quality of life impact than ustekinumab. Presented at AAD 2017; Poster #4800.

34. Puig L, Griffiths CE, Gilloteau I, et al. Secukinumab provides greater improvement in quality of life, work productivity, and daily activity than ustekinumab in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis: a structural equation modeling approach using the CLEAR Study. Presented at AAD 2017; Poster #5447.

35. Gottlieb AB, Lebwohl M, Gilloteau I, et al. Secukinumab provides greater skin clearance and improvement in skin-related quality of life than ustekinumab for biologic-naïve patients with psoriasis: results from the CLEAR 52-week study. Presented at AAD 2017; Poster #5458.

36. Feldman S, Green L, Kimball AB, et al. Secukinumab improves scalp pain, itching, scaling, and quality of life in patients with moderate to severe scalp psoriasis. Presented at AAD 2017; Poster #4905.

37. Reich K, Arenberger P, Mrowietz U, et al. Secukinumab shows high and sustained efficacy in nail psoriasis: 1.5 year results from the TRANSFIGURE study. Presented at AAD 2017; Poster #5501.

38. Bissonnette R, Luger T, Thaçi D, et al. Secukinumab provides sustained improvements in dermatology-specific quality of life in moderate to severe psoriasis patients through 3 years of treatment: results from the SCULPTURE extension study. Presented at AAD 2017; Poster #4223.

39. Gottlieb AB, Sullivan J, Kubanov A, et al. Secukinumab shows significant improvement in patient-reported outcomes in difficult-to-treat palmoplantar psoriasis: 1.5 year data from the GESTURE study. Presented at AAD 2017; Poster #5232.

40. Blauvelt A, Reich K, Warren RB, et al. Secukinumab retreatment shows rapid recapture of treatment response: an analysis of a phase 3 extension trial in psoriasis. Presented at AAD 2017; Poster #4879.

41. Georgakopoulos JR, Ighani A, Yeung J. Efficacy and safety of secukinumab (IL-17A inhibitor) in treating moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in two real-world academic dermatology clinics: a Canadian multicenter retrospective study. Presented at AAD 2017; Poster #4443.

42. Vender R, Yanofski H, Boucher A, et al. Early real-world effectiveness of secukinumab in the treatment of psoriasis in Canada: retrospective analysis of patient support program data. Presented at AAD 2017; Poster #5756.

43. Gottlieb AB, Strober B, Armstrong AW, et al. Secukinumab in psoriasis patients with concurrent psoriatic arthritis: patient-reported outcomes in the corrona psoriasis registry. Presented at AAD 2017; Poster #4432.

44. Gottlieb AB, Strober B, Armstrong AW, et al. Secukinumab in psoriasis patients with concurrent psoriatic arthritis: demographics and disease characteristics in the Corrona Psoriasis Registry. Presented at AAD 2017; Poster #4511.

45. Lebwohl M, Strober B, Menter A, et al. Phase 3 studies comparing brodalumab with ustekinumab in psoriasis. N Engl J Med 2015; 373(14):1318-28.

46. Papp KA, Reich K, Paul C, et al. A prospective phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of brodalumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 2016; 175(2):273-86.

47. SILIQ™ (brodalumab) prescribing information (USA). Revised 02/2017.

48. Yamauchi P, Papp KA, Hsu S, et al. Improvement in scalp psoriasis with brodalumab in a randomized placebo-controlled phase 3 study (AMAGINE-1). Presented at AAD 2017; Poster #5247

49. Lebwohl MG, Green L, Hsu S, et al. Improvement in nail psoriasis with brodalumab in phase 3 trials. Presented at AAD 2017; Poster #5296.

50. Papp KA, Lebwohl MG, Bhatt V, et al. Rapid onset of efficacy in patients with psoriasis treated with brodalumab versus ustekinumab: A pooled analysis of data from two phase 3 randomized clinical trials (AMAGINE-2 and AMAGINE-3). Presented at AAD 2017; Poster #5138.

51. Blauvelt A, Lebwohl MG, Green LJ, et al. Median time to treatment response in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis treated with brodalumab 210 mg or ustekinumab: A pooled analysis of data from two phase 3 randomized clinical trials (AMAGINE-2 and AMAGINE-3). Presented at AAD 2017; Poster #5092.

52. Papp KA, Lebwohl MG, Krueger JG, et al. Impact of previous biologic use and failure on efficacy of brodalumab and ustekinumab: A pooled analysis of data from two phase 3 randomized clinical trials in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis (AMAGINE-2 and AMAGINE-3). Presented at AAD 2017; Poster #4978.

53. Lebwohl M, Papp KA, Wu JJ, et al. Psychiatric adverse events in brodalumab psoriasis studies. Presented at AAD 2017; Poster #4908.

54. Strober B, Eichenfield LF, Armstrong A, et al. Overview of adverse cardiovascular events in the brodalumab psoriasis studies. Presented at AAD 2017; Poster #4758.

55. Gottlieb AB, Blauvelt A, Leonardi C, et al. Certolizumab pegol treatment for chronic plaque psoriasis: 16-week primary results from two phase 3, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled studies. Presented at AAD 2017; Presentation #5077.

56. Bissonnette R, Harel F, Krueger JG, et al. TNF-a antagonist and vascular Inflammation in patients with psoriasis vulgaris: a randomized placebo-controlled study. Presented at AAD 2017; Presentation #5076.

57. Gelfand J. Getting to the heart (and other comorbidities) of psoriasis. Presented at AAD 2017; Plenary Lecture.

58. Leonardi C, Kelleher C, Tang H, et al. Evaluation of CHS-0214 as a proposed biosimilar to etanercept for the treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis: one-year results from a randomized, double-blind global trial. Presented at AAD 2017; Poster #5158.

59. Blauvelt A, Fowler JF, Schuck E, et al. A randomized, double-blind, multicenter study to compare the efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity of a proposed adalimumab biosimilar (GP2017) with originator adalimumab in patients with moderate-to-severe chronic plaque psoriasis. Presented at AAD 2017; Poster #5224.

60. Langley R & Gordon K. Which biologic to start first: an IL-17/IL-23 or aTNF blocker. A debate at AAD 2017.

Copyright 2017 STA HealthCare Communications Inc. All rights reserved. This program is published by STA HealthCare Communications Inc. as a professional service funded by Janssen Inc. The information and opinions contained herein reflect the views and experience of the authors and not necessarily those of Janssen Inc. or STA HealthCare Communications Inc. Any products mentioned herein should be used in accordance with the prescribing information contained in their respective product monographs.