Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease (ADPKD):

A Review for Primary Care Physicians

|

Ahsan Alam, MD, CM, MS, FRCPC Associate Professor of Medicine, Division of Nephrology and Multiorgan Transplant Program Royal Victoria Hospital–McGill University Health Centre Montreal, Quebec |

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) is the most common genetic cause of kidney failure, and the fourth most common reason for patients to progress to dialysis. The estimated prevalence is one in 400 to one in 1,000 live births, which would be estimated to affect more than 30,000 Canadians. This makes it more common than Down syndrome, hemophilia A, Huntington’s disease, and cystic fibrosis combined.4

There are currently two known disease-causing genes, PKD1 and PKD2, which encode for the polycystin 1 and polycystin 2 proteins, respectively. PKD1 gene mutations account for the majority (75-85%) of all ADPKD cases.8 These proteins co-localize to the primary cilium of the kidney tubular epithelial cells and, when polycystin activity is sufficiently reduced, there is disruption of normal intracellular calcium signalling. The consequences are cell proliferation, development of cystic dilatations of the renal tubule, fluid secretion and growth of cysts, which compress and then irreversibly destroy the normal kidney parenchyma, with ensuing loss of kidney function. Patients with PKD1 mutations generally have a more rapid course of renal disease progression, with half reaching dialysis in the sixth decade of life and, on average, a decade earlier than those with PKD2. It must be noted, however, that there remains considerable inter- and intra-familial variability with respect to kidney disease progression, and other clinical and environmental risk factors can influence the disease course.3

Diagnosis

The conventional method and mainstay for diagnosis of ADPKD is abdominal ultrasound. Ultrasound criteria are available that can be used irrespective of the PKD genotype. The diagnosis can be confirmed (with 100% positive predictive value) in an individual aged 15-39 years if there are at least three cysts in either or both kidneys, at least two cysts per kidney for someone aged 40-59 years, and at least four cysts per kidney in anyone aged 60 years or older. If an individual has fewer than two kidney cysts after the age of 40 years, ADPKD can be safely excluded.

The consequences of ADPKD extend beyond the loss of kidney function and progression to kidney failure.

It is important to only apply these criteria for those with a family history of ADPKD.10 For cases where family history is unavailable or absent, well-validated criteria do not exist to confirm a diagnosis but may be strongly supported by the presence of numerous, bilateral kidney cysts (i.e., at least 20) or evidence of extra-renal involvement. When there is uncertainty regarding the diagnosis, genetic testing may be appropriate, which can also provide prognostic information about disease-progression risk.2

Impact

The consequences of ADPKD extend beyond the loss of kidney function and progression to kidney failure. Other renal manifestations include hypertension, kidney pain and discomfort (reported in 60% of patients with the disease), kidney stones (20%), cyst hemorrhage, and cyst infections. There are also extra-renal manifestations of ADPKD that may include polycystic liver disease, cystic involvement of other organs such as the pancreas and seminal tract, cardiac valvular involvement, abdominal-wall hernias, and diverticular disease.2 Another important complication is the development of intracranial aneurysms. Although relatively uncommon (occurring in approximately 8%), the consequence can be severe. Screening with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) angiography is indicated in those with stroke-like symptoms or a severe or atypical headache, those with a family history of aneurysm or sudden death, those in a high-risk occupation (e.g., pilot), or before a major surgery or use of long-term anticoagulation. Some may recommend it be done routinely at the time of diagnosis or to alleviate the anxiety of a patient who is worried about this.11 The impact of ADPKD has even broader implications as those affected may deal with the psychological burden of a chronic disease; concerns for their children or planning a family; chronic pain; or anxiety regarding their eventual need for dialysis or kidney transplantation. Insurability and the impact on school and work can also be important.

ADPKD: A Progressive Disease

ADPKD is a progressive disease that can take several decades before the loss of kidney function. Early in the course of the disease, the destruction of kidney tissue by expanding cysts is usually compensated by glomerular hyperfiltration. Only late in the course of the disease (i.e., after much of the normal kidney parenchyma has been irreversibly destroyed) is glomerular hyperfiltration no longer able to compensate adequately and GFR starts to decline rapidly. This makes the use of GFR an insensitive marker of disease progression.14 Kidney enlargement or increases in total kidney volume can be tracked and represent an earlier biomarker of eventual kidney function decline and complications.7,9 The natural history of ADPKD is best demonstrated from the Consortium of Radiologic Imaging Studies of Polycystic Kidney Disease (CRISP), a National Institutes of Health (NIH)-sponsored prospective, observational study of 241 patients with ADPKD for over 14 years. At enrollment, these patients were between 15 and 45 years of age and had preserved kidney function, but most had a risk factor for progression, such as hypertension or proteinuria. The study demonstrated that the rate of kidney growth is variable between individuals; however, larger total kidney volume at baseline predicted a lower GFR after eight years, and correlated with complications of disease (e.g., hypertension, gross hematuria, and proteinuria).1,6

Factors that are prognostic and portend an unfavorable association with more rapid renal progression include the genotype (PKD1 disease and truncating mutation), a family history of early-onset end-stage renal disease (ESRD), evidence of premature GFR decline, increased total kidney volume, presence of early-onset hypertension or urological complications, elevated uric acid, and albuminuria or overt proteinuria.13 Extrapolations from animal studies also raise concerns over increased caffeine intake and low water intake.

Treatment Options

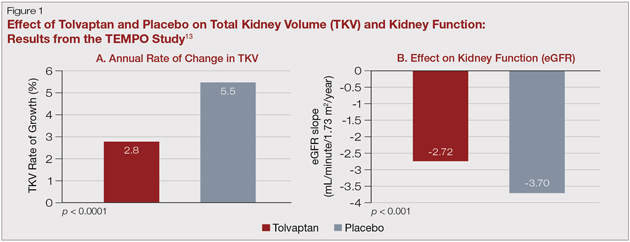

Better understanding of the intracellular pathways that stimulate cyst proliferation and growth have led to several studies in ADPKD patients at risk of progression. Phase 3 randomized clinical trials using mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors (sirolimus and everolimus) did not show efficacy for slowing total kidney volume growth and preserving GFR. Somatostatin analogues have shown some promise in preliminary study. However, the Tolvaptan Efficacy and Safety in Management of Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease and Its Outcomes

...active treatment [with tolvaptan] slowed growth of kidney volume and also suggested a slower deterioration in GFR...

(TEMPO) 3:4 study, which randomized 1,445 patients to receive the vasopressin-2 receptor antagonist, tolvaptan, or placebo over a three-year study period showed that active treatment slowed growth of kidney volume (Fig.1A) and also suggested a slower deterioration in GFR (Fig. 1B) and an improvement in pain. There was a greater number of side effects related to the medication, (e.g., polyuria, thirst, gout and, importantly, hepatitis that required discontinuation of the medication).5,15 Tolvaptan has been approved by Health Canada and is currently the only disease-modifying pharmacologic therapy for patients with ADPKD. In addition, the Halt Progression of Polycystic Kidney Disease (HALT-PKD) clinical trial supported a more aggressive BP goal (home BP 95/60 mmHg to 110/75 mmHg) for those with ADPKD who are less than 50 years of age, with an eGFR > 60 mL/min and without significant cardiovascular comorbidity.11

There is great optimism due to the landmark clinical advances that have taken place over the past decade, in not only better understanding the pathophysiology of ADPKD, but also the targeted interventions that can modify disease progression. This highlights the importance of identifying all patients with ADPKD, whether subclinical, those at an early stage of the disease with or without symptoms, and those with evidence of kidney enlargement before they lose significant kidney function. An expert consensus has been published in Canada that recommends that all ADPKD patients should be referred to a nephrologist to determine the risk of progression and eligibility of treatment.13

An expert consensus has been published in Canada that recommends that all ADPKD patients should be referred to a nephrologist to determine the risk of progression and eligibility of treatment.

In many cases, those at low risk for progression may be followed and risk-stratified at one- or two-year intervals by a nephrologist. For those prescribed targeted therapy or enrolled in a clinical study, nephrology follow-up may be more frequent.

Conclusion

Over the past decade, important strides have been made in better understanding the pathophysiology and risk factors for disease progression in those with ADPKD. With innovative therapies that may modify the trajectory of renal progression, there is now hope for those who suffer from ADPKD.

References

1. Chapman A, Guay-Woodford L, Grantham J, et al. Renal structure in early autosomal- dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD): The consortium for radiologic imaging studies of polycystic kidney disease (CRISP) cohort. Kidney Int 2003; 64:1035-45.

2. Chapman AB, Devuyst O, Eckardt KU, et al. Autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD): executive summary from a kidney disease: improving global outcomes (KDIGO) controversies conference. Kidney Int 2015 Jul 31; 88(1):17-27.

3. Cornec-Le Gall E, Audrezet MP, Chen JM, et al. Type of PKD1 mutation influences renal outcome in ADPKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 2013; 24: 1006-13.

4. Gabow PA. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 1993; 329(5):332-42.

5. Gansevoort RT, Arici M, Benzing T, et al.. Recommendations for the use of tolvaptan in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: a position statement on behalf of the ERA-EDTA working groups on inherited kidney disorders and European renal best practice. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2016; 31 (3): 337-348.

6. Grantham JJ, Chapman AB, Torres VE. Volume progression in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: the major factor determining clinical outcomes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2006; 1:148-57.

7. Grantham JJ, Torres VE. The importance of total kidney volume in evaluating progression of polycystic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 2016; 12(11): 667-77.

8. Hateboer N, v Dijk MA, Bogdanova N, et al. Comparison of phenotypes of polycystic kidney disease types 1 and 2. European PKD1-PKD2 study group. Lancet 1999; 353:103-7.

9. Irazabal MV, Rangel LJ, Bergstralh EJ, et al. Imaging classification of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: a simple model for selecting patients for clinical trials. J Am Soc Nephrol 2015; 26:160-72.

10. Pei Y, Obaji J, Dupuis A, et al. Unified criteria for ultrasonographic diagnosis of ADPKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2009; 20(1):205-12.

11. Perrone RD, Malek AM, Watnick T. Vascular complications in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 2015;11(10):589-98.

12. Schrier RW, Abebe KZ, Perrone RD. Blood pressure in early autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Eng J Med 2015; 372: 975-7.

13. Soroka S, Alam A, Bevilacqua M, et al. Assessing risk of disease progression and pharmacological management of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: a Canadian expert consensus. Can J Kidney Health Dis 2017; 2054358117695784.

14. Tangri, N., Hougen, I., Alam, A., et al. Total kidney volume as a biomarker of disease progression in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Can J Kidney Health Dis 2017; 2054358117693355.

15. Torres VE, Chapman AB, Devuyst O, et al. Tolvaptan in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 2012; 367:2407-18.