|

Louis WC Liu University Health Network, |

John Marshall Department of Medicine and Farncombe |

||

|

Keith McIntosh Western University, |

Phuong Nguyen Independent practice, |

||

|

Yvonne Tse University Health Network, |

Kathryn Woodman Department of Medicine and Farncombe |

ABSTRACT

Background: Primary care physicians (PCP) play an integral role in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) management, but care pathways and clinical guidelines designed with the realities of primary care in mind

are lacking. The objective of this study was to develop a care pathway for IBS diagnosis and treatment

in primary care practices in Canada.

Methods: A steering committee comprising gastroenterologists and one PCP reviewed the latest level

I-III evidence and drafted the decision tool through an iterative process, based on this evidence along

with clinical experience. The recommended pharmacological therapies are supported by level I evidence.

Results: The timely diagnosis and effective treatment of IBS are essential for patients to achieve

improved symptomatology and quality of life. We recommend initiating investigations and treatment

in parallel to reduce delays, a concise three-visit format, and the use of both nonpharmacological and

pharmacological therapies.

Conclusions: This pathway will support PCPs in their efforts to improve outcomes for patients with

IBS in Canada.

Background

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a disorder of gut-brain interaction that is characterized by abdominal pain and diarrhea or constipation.1 Most individuals with IBS are frequently in pain, and one-quarter have constant pain.2 The pathophysiology includes activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and altered neurological circuitry leading to lowered thresholds for pain perception.3-5 Disease subtypes include IBS with diarrhea (IBS-D), IBS with constipation (IBS-C), IBS with a mixed stool pattern (IBS-M), and unclassified IBS (IBS-U).6-8 Estimates in Canada from a recent survey show an IBS prevalence of 4.2%.9

Family practitioners have integral roles in IBS management.10 The chronic nature of the condition requires continuity of care and a productive patient-physician relationship.11-13 However, many primary care physicians (PCPs) lack confidence in diagnosing and treating IBS and associate the condition with complexity and uncertainty.14 The presentation overlaps with other gut-brain disorders, celiac disease, and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)14-16 and may exist on a continuum with other functional bowel disorders.17

American PCPs identified IBS as one of the most difficult chronic diseases to treat, and patients often receive therapies that lack proven efficacy.18-19 These challenges indicate a need for greater clinician awareness of IBS diagnosis and treatment.20 Although clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) are available, some are out of date, while others are discordant.21 Few guidelines have specifically aimed to improve the efficiency of IBS treatment in Canadian primary care. We developed a decision tool and practice pathway that incorporates high-quality evidence and supports non-gastroenterologists in improving IBS management with the objectives of:

- obtaining a timely, positive diagnosis;

- reducing the time to treatment;

- reducing unnecessary testing;

- integrating evidence-based therapies into practice;

- increasing the efficiency of referral, including helping non-gastroenterologists to identify patients who require a referral for specialized care.

Methods

The development of practice recommendations was undertaken as a collaborative effort between practitioners, the authors of the study, at academic hospital centres in Ontario, including Toronto Western Hospital, St. Joseph’s Healthcare Hospital, and McMaster University. The goal was to assemble an expert panel of gastroenterologists and PCPs to discuss the unmet needs in IBS management in primary care. A steering committee was formed in November 2022, comprising five gastroenterologists and one PCP. Members of the panel practice in diverse geographical regions in Ontario and have expertise in gastric motility, demonstrated by their track records of peer-reviewed publications, academic appointments, leadership on clinical trials, and involvement in medical education.

The committee reviewed the latest evidence, aligned on the aims, and drafted the decision tool and practice pathway based on their expertise and clinical practice considerations. Two face-to-face meetings and several virtual meetings were conducted in the process of clinical practice pathway composition. Through two rounds of review, revision, and discussion, the group agreed on a practical tool to aid PCP management of IBS in October 2023. The final tool was developed through an iterative process and was reviewed and edited by all participants.

Results

A. IBS Treatment Pathway Overview

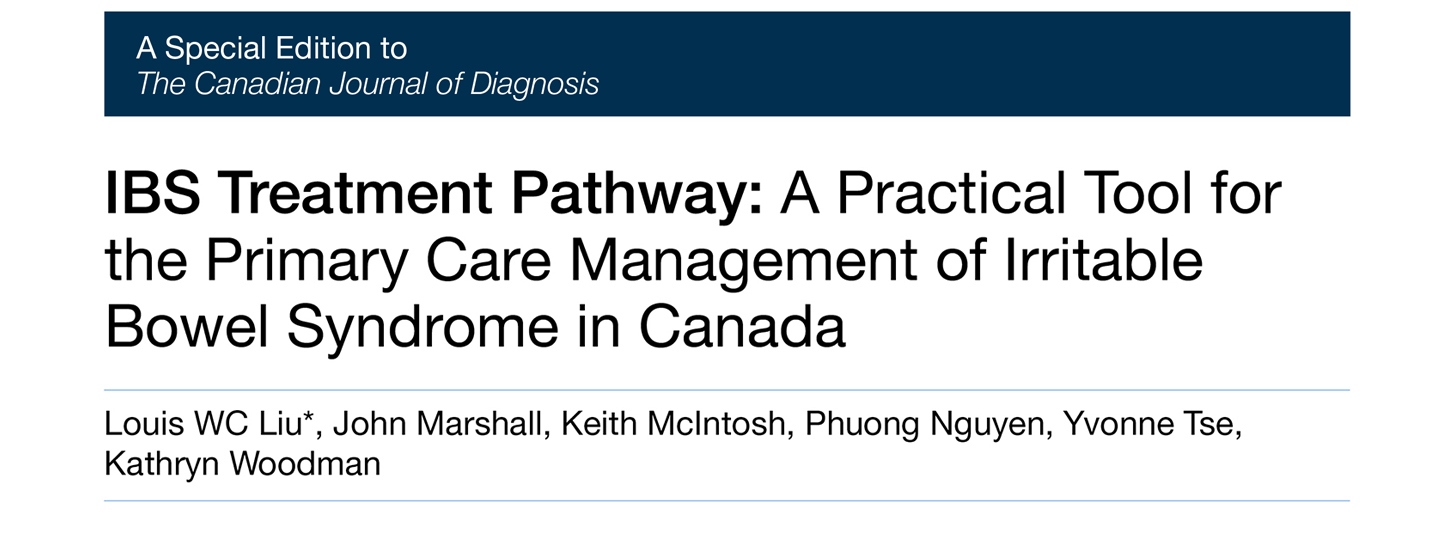

The recommended pathway for a patient with suspected IBS involves three visits (Figure 1):

- Visit 1: Assess for IBS symptoms and alarm features. Initiate, in parallel, investigations and treatments (nonpharmacological and pharmacological). Refer to a gastroenterologist if alarm features are present.

- Visit 2: Assess treatment response and discuss test results (refer to appropriate specialists for abnormal test results). Adjust therapy if necessary.

- Visit 3: Reassess treatment response. If symptoms are refractory, consider referral to a gastroenterologist.

B. Visit 1

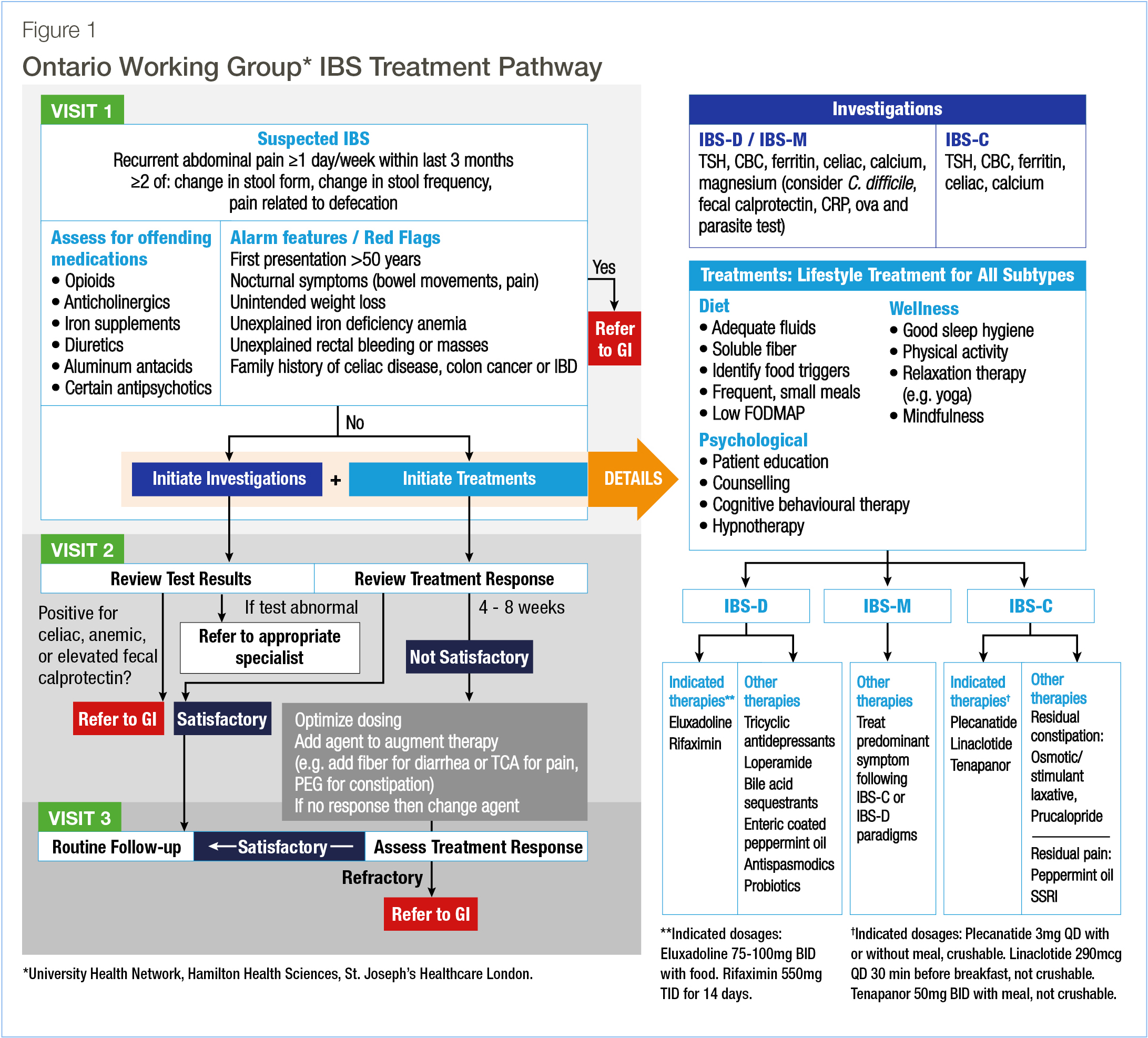

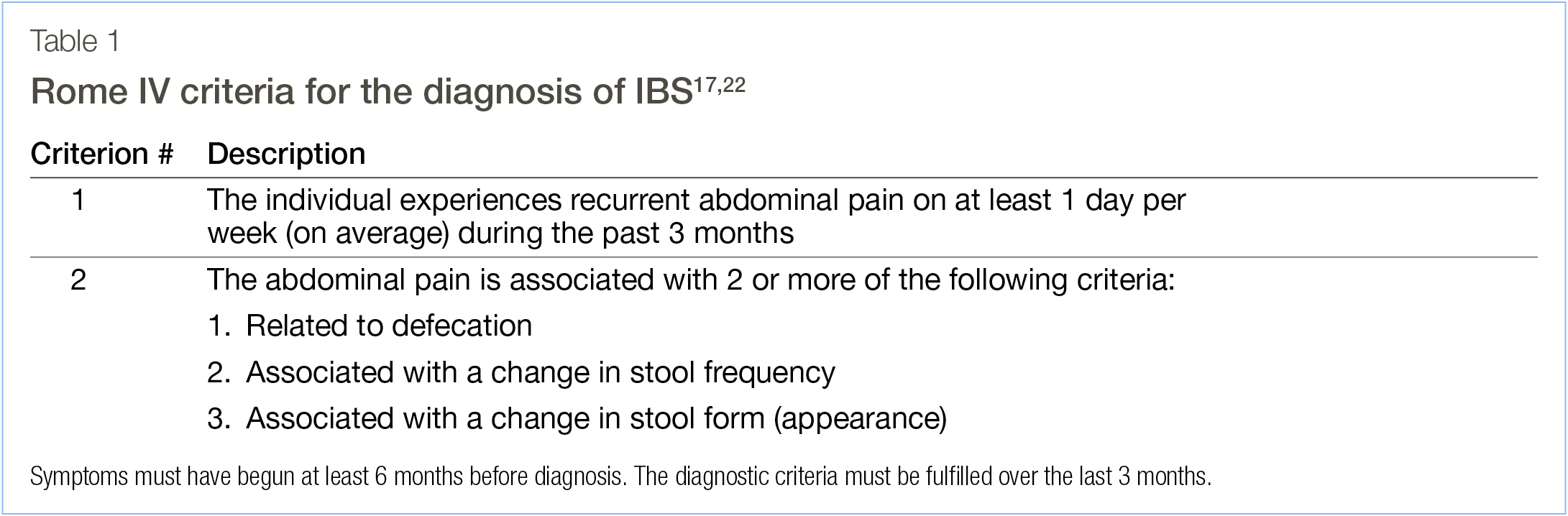

Patients with suspected IBS based on the Rome IV criteria17,22 (Table 1) should undergo a physical examination and provide a detailed medical history. The IBS subtype should be assessed (Table 2) and the stool form should be described using the Bristol scale.17,22,23 Abnormal stools, fecal urgency, and incomplete evacuation occur frequently in IBS.24

Medications should be reviewed with attention to any that are associated with gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms. Alarm features that could indicate malignancy or a non-IBS etiology may require further investigation. These include a first presentation over 50 years old, nocturnal symptoms, unintended weight loss, unexplained rectal bleeding, unexplained iron deficiency anemia, and a family history of celiac disease, colorectal cancer (CRC) or IBD.26 Patients with these features should be referred to a gastroenterologist. If alarm features are absent, investigation and treatment for IBS (including lifestyle modifications and pharmacological therapies) should be initiated in parallel to enable the patient to access treatment rapidly. To assess the response at subsequent visits, the patient may track symptom severity using a diary.27 It is also important to discuss diet, sleep hygiene, and physical activity. Mental health issues should be addressed, and psychological interventions should be considered for all patients.28-30

Finally, routine colonoscopy is not recommended, and patients should receive CRC screening according to the guidelines for the general population.31,32

Recommended investigations

As part of the workup, we recommend a complete blood count (CBC) along with serum thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), ferritin, and calcium. The CBC and ferritin can exclude findings requiring additional investigation.10 Celiac disease symptoms overlap with those of IBS, and we recommend serologic testing.26,33 Total IgA should be measured to exclude IgA deficiency as a cause of false-negative celiac serology.

For individuals with symptoms of IBS-D or IBS-M, we recommend tests for enteric infection (stool culture and sensitivity, ova and parasites, and Clostridium difficile toxin), fecal calprotectin (FC), C-reactive protein (CRP), and magnesium. Enteric infection can lead to post-infection IBS.34,35 CRP and FC can be used to exclude inflammatory conditions such as IBD.10,26

Recommended treatment – nonpharmacological

Nonpharmacological therapy is an essential component of treatment.29,36 Recommendations include consuming adequate fluids and soluble fibre; and a diet low in fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (low-FODMAP) should be considered.26 Over half of individuals with IBS have food triggers, most commonly dairy, legumes, biogenic amines, and fatty foods.26 These should be identified and minimized. Physical activity can improve symptoms, and we also recommend addressing sleep hygiene.37-40

Psychological interventions are also recommended.26,29 For example, cognitive behavioral therapy attenuates pain and improves mood in individuals with IBS.28,30,41-45 Beneficial effects on mood and GI symptoms have also been reported for gut-directed hypnotherapy, meditation, and relaxation training.28,30,41,13,46,47

Nonpharmacological therapies are, however, limited in managing global symptoms; pharmacological therapy is therefore necessary for most patients.26

Recommended treatment – pharmacological

Treatment should be initiated while investigations are in progress. We recommend choosing one of the indicated therapies (Figure 1) approved by Health Canada, demonstrating benefits in reducing pain and global symptoms. Over-the-counter (OTC) medications and off-label therapies are also available, but these agents have limited benefits, and clinical trials have reported mixed results.5

For IBS-D, we recommend the opioid receptor agonist/antagonist eluxadoline or the antibiotic rifaximin. Other therapies, such as tricyclic antidepressants, loperamide, antispasmodics, probiotics, bile acid sequestrants, and peppermint oil may also be considered. For IBS-C, we recommend plecanatide, linaclotide, or tenapanor. An osmotic laxative, a stimulant laxative, or prucalopride may be considered for residual constipation, and peppermint oil or a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) for individuals who continue to experience pain. The supporting evidence, mechanisms of action, and dosing information for the indicated pharmacological therapies are described in the Supplementary Information.

C. Visits 2 and 3

The second visit should take place after tests have been completed and after 4-8 weeks of treatment. If the results show celiac disease, anemia, or elevated FC, the patient should be referred to a gastroenterologist. If the patient has responded well, treatment should be continued. Otherwise, the agent may be changed, the dose adjusted, or additional agent(s) added.

The treatment response should be reassessed at the third visit. If satisfactory, no further adjustments are necessary. If there has been partial response, further optimization of treatment is recommended. However, if the symptoms are refractory, we recommend referral to a gastroenterologist.

Discussion

A. Choosing a pharmacological therapy

Family practitioners should be aware of the current therapies available for IBS and the clinical data supporting their use. Here we discuss the evidence supporting the recommended IBS therapies, and considerations for choosing a therapy.

Although OTC medications are frequently used, these agents have limited benefit for pain and global symptoms, and their long-term safety is unclear.5,48 For example, in a randomized trial, polyethylene glycol relieved constipation but did not decrease pain.49 Off-label therapies provide modest benefits, but symptom relief is often inadequate.5,50,51 In a meta-analysis, peppermint oil and tricyclic antidepressants demonstrated efficacy for global symptoms and pain, but some trials were of short duration and lacked rigour, creating uncertainty (refer to Supplementary Information for details).50 Therefore, we recommend first line therapies that are supported by clear evidence and approved by Health Canada.

IBS-D

Health Canada-indicated IBS-D therapies include rifaximin and eluxadoline. Rifaximin is a broad-spectrum antibiotic that alters gut permeability.52 Individuals treated with rifaximin experienced significant relief from IBS symptoms, including bloating and pain.53 Its safety profile is similar to placebo,53 with benefit lasting up to 22 weeks and no evidence of resistance.54 The recommended dose is 550 mg orally three times a day for 14 days.55

Eluxadoline is an opioid receptor agonist/antagonist that reduces GI motility and visceral hypersensitivity.56 Phase 3 clinical trials showed decreases in pain and improvements in stool consistency.57 There was no indication of symptom worsening or withdrawal after treatment was stopped.57 The recommended dose is 100 mg orally twice daily, which may be reduced to 75 mg twice daily for tolerability.58 Patients 65 years of age and older should start at 75 mg, increasing to 100 mg if well tolerated.58 However, eluxadoline is contraindicated in patients with significant hepatic impairment, excessive alcohol consumption, or cholecystectomy; refer to Supplementary Information for details.58

IBS-C

Health Canada-indicated IBS-C therapies include the guanylate cyclase-C (GC-C) agonists linaclotide and plecanatide, which accelerate intestinal transit,59 and tenapanor, an inhibitor of the sodium/hydrogen exchanger isoform 3 (NHE3), which increases intestinal sodium and fluid.60 The efficacy of linaclotide is supported by a phase 3, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial and two open-label trials of up to 78 weeks.61,62 The recommended dose is 290 μg orally once daily.63 Plecanatide has demonstrated efficacy in two phase 3 trials, and its long-term safety was demonstrated in a 53-week open-label trial.64,65 The recommended dose is 3 mg orally once daily.66 Finally, the long-term safety of tenapanor was demonstrated over 52 weeks in two phase 3 trials.67-69 The recommended dose is 50 mg orally twice daily (refer to the Supplementary Information for details).70

The benefits and safety of the indicated therapies have been established in randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 clinical trials.53,54,57,61,62,64,65,67-69 However, these drugs have not been compared in head-to-head trials, and the available meta-analyses offer limited support in choosing among the medications.71-73 Given the current evidence, it is difficult to select a single best choice. Instead, the clinician and patient should participate in shared decision-making, considering the patient’s previous experiences, drug availability, routes and schedules of administration, and cost.

B. Applying the pathway in practice

The significance of PCPs in alleviating the impact of IBS within the community is pivotal and cannot be overemphasized.74 However, PCPs are often challenged to reach a timely, positive diagnosis.14 On average, it takes four years for a patient to receive a definitive diagnosis and up to six years from the onset of symptoms.2,19 As a result, many patients report feelings of stigma, and a lack of support and empathy.19,75

The Canadian Association of Gastroenterology (CAG) has published CPGs,26 and guidance for PCPs is available.8,76-79 Yet, not all are applicable to primary care.21 The pathway described herein will increase clinicians’ awareness of the best practices for IBS management in Canada, including the optimal use of nonpharmacological and pharmacological therapies, which should both be implemented early during treatment. The focus on symptom-based criteria, along with limited testing and recommendations for newer therapies that are supported by strong evidence will help PCPs to handle diagnosis and treatment confidently.19,36

A unique feature of this pathway is that tests and treatment will be carried out in parallel. It is safe to initiate treatment without waiting for test results, which may be time-consuming. Furthermore, exhaustive diagnostic testing is not necessary.26,78,79 Hence, we recommend limited testing and use of the symptom-based Rome IV criteria (Table 1); no imaging is necessary except in specific circumstances. Treatment should be adjusted based on the test results and treatment responses. We also support building a strong patient-provider relationship based on empathy and education.26,79

While this pathway is designed for PCPs, who manage most IBS patients, referral to a gastroenterologist is recommended if a patient has alarm features or if tests indicate celiac disease, anemia, IBD, possible malignancy, or if symptoms are refractory to therapy, including changing agents and optimizing dosing.

C. Limitations

These recommendations are based on expert opinion and clinical experience in Ontario as well as recent clinical data. Although the decision tool may apply throughout Canada, some recommendations may not be congruent with local best practices. The application of some of the recommendations will depend on regional resources, including specialist availability, access to therapeutic agents, and insurance coverage.

Conclusions

We report an evidence-based decision tool and treatment pathway for IBS diagnosis and treatment in Canadian primary care. The pathway is simple and practical such that it can be efficiently integrated into practice.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

CBC: Complete blood count

CPG: Clinical practice guideline

CRC: Colorectal cancer

CRP: C-reactive protein

FC: Fecal calprotectin

GI: Gastrointestinal

IBS: Irritable bowel syndrome

IBD: Inflammatory bowel disease

IBS-C: IBS with constipation

IBS-D: IBS with diarrhea

IBS-M: IBS with mixed symptoms

IBS-U: unclassified IBS

OTC: Over the counter

PCP: Primary care physician

DECLARATIONS

COMPETING INTERESTS

LWCL received honoraria for academic lectures from AbbVie, Bausch Health,Knight Therapeutics Inc, Lupin Pharmaceutical, Avir Pharma, and Medtronic; and participated on advisory boards for AbbVie, Bausch Health, and Knight Therapeutics Inc. JM received consulting fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Astra Zeneca, Bausch Health, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celltrion, Eli Lilly, Ferring, Fresenius Kabi, Janssen, Lupin Pharmaceutical, Organon, Paladin, Pfizer, Pharmascience, Roche, Sandoz, Takeda, Teva, and Viatris; and honoraria for academic lectures from AbbVie, Amgen, Bausch Health, Ferring, Fresenius Kabi, Janssen, Lupin Pharmaceutical, Organon, Pfizer, Pharmascience, Roche, Takeda, Viatris. KM received honoraria for academic lectures from Knight Therapeutics Inc and Lupin Pharmaceutical. PN received honoraria for academic lectures from AbbVie, Alexion, AstraZeneca, Bausch Health, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eisai, Eli Lilly, GSK, HLS, Janssen, Knight Therapeutics Inc., Merck, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, and Sanofi; and participated on advisory boards for AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Bausch Health, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, GSK, HLS, Knight Therapeutics Inc., Merck, Novo Nordisk. YT received consulting fees from Knight Therapeutics Inc. and Medtronic; honoraria for academic lectures from Bausch Health and Knight Therapeutics Inc.; and participated on advisory boards for Knight Therapeutics Inc. KW received honoraria for consultancy from Bausch Health.

FUNDING

Funding for assistance with writing and editing the manuscript was provided by Bausch Health Canada.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors extend their gratitude to Margaret Johnson, Ph.D., and STA Healthcare Communications (Montréal, Canada) for their assistance with writing and editing.

REFERENCES

1. Ford AC, Sperber AD, Corsetti M, Camilleri M. Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Lancet. 2020;396(10263):1675-88.

2. Drossman DA, Morris CB, Schneck S, Hu YJ, Norton NJ, Norton WF, et al. International Survey of Patients with Ibs: Symptom Features and Their Severity, Health Status, Treatments, and Risk Taking to Achieve Clinical Benefit. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43(6):541-50.

3. Moloney RD, Johnson AC, O’Mahony SM, Dinan TG, Greenwood-Van Meerveld B, Cryan JF. Stress and the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis in Visceral Pain: Relevance to Irritable Bowel Syndrome. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2016;22(2):102-17.

4. Raskov H, Burcharth J, Pommergaard HC, Rosenberg J. Irritable Bowel Syndrome, the Microbiota and the Gut-Brain Axis. Gut Microbes. 2016;7(5):365-83.

5. Black CJ, Ford AC. Best Management of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Frontline Gastroenterology. 2021;12(4):303-15.

6. Kopczyn´ska M, Mokros Ł, Pietras T, Małecka-Panas E. Quality of Life and Depression in Patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Prz Gastroenterol. 2018;13(2):102-8.

7. Holtmann GJ, Ford AC, Talley NJ. Pathophysiology of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;1(2):133-46.

8. Alberta Health Services. Primary Care Supports: Digestive Health Strategic Clinical Networktm. [updated 2023. Available from: https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/scns/ Page13909.aspx.

9. Sperber AD, Bangdiwala SI, Drossman DA, Ghoshal UC, Simren M, Tack J, et al. Worldwide Prevalence and Burden of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders, Results of Rome Foundation Global Study. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(1):99-114.e3.

10. Cash BD. Understanding and Managing Ibs and Cic in the Primary Care Setting. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2018;14(5 Suppl 3):3-15.

11. Chandar AK. Diagnosis and Treatment of Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Predominant Constipation in the Primary-Care Setting: Focus on Linaclotide. Int J Gen Med. 2017;10:385-93.

12. Harkness EF, Harrington V, Hinder S, O’Brien SJ, Thompson DG, Beech P, et al. Gp Perspectives of Irritable Bowel Syndrome – an Accepted Illness, but Management Deviates from Guidelines: A Qualitative Study. BMC Family Practice. 2013;14(1):92.

13. Tan ZE, Tan YQ, Lin H, How CH. Irritable Bowel Syndrome: An Approach for Primary Care Physicians. Singapore Med J. 2022;63(7):367-70.

14. Andresen V, Whorwell P, Fortea J, Auzière S. An Exploration of the Barriers to the Confident Diagnosis of Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Survey among General Practitioners, Gastroenterologists and Experts in Five European Countries. United European Gastroenterol J. 2015;3(1):39-52.

15. Goldstein RS, Cash BD. Making a Confident Diagnosis of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2021;50(3):547-63.

16. Camilleri M. Diagnosis and Treatment of Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Review. Jama. 2021;325(9):865-77.

17. Mearin F, Lacy BE, Chang L, Chey WD, Lembo AJ, Simren M, et al. Bowel Disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016.

18. Longstreth GF, Burchette RJ. Family Practitioners’ Attitudes and Knowledge About Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Effect of a Trial of Physician Education. Family Practice. 2003;20(6):670-4.

19. The Gastrointestinal Society. Ibs Global Impact Report 2018. [updated April 3, 2018. Available from: https://badgut.org/ibs-global-impact-report-2018/.

20. Halpert AD. Importance of Early Diagnosis in Patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Postgraduate Medicine. 2010;122(2):102-11.

21. Moayyedi P, Marsiglio M, Andrews CN, Graff LA, Korownyk C, Kvern B, et al. Patient Engagement and Multidisciplinary Involvement Has an Impact on Clinical Guideline Development and Decisions: A Comparison of Two Irritable Bowel Syndrome Guidelines Using the Same Data. Journal of the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology. 2019;2(1):30-6.

22. Rome Foundation. Rome Iv Diagnostic Criteria for Disorders of Gut-Brain Interaction (Dbgi). [updated January 16, 2016. Available from: https://theromefoundation.org/rome-iv/rome-ivcriteria/.

23. Lewis SJ, Heaton KW. Stool Form Scale as a Useful Guide to Intestinal Transit Time. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32(9):920-4.

24. Heaton KW, Ghosh S, Braddon FE. How Bad Are the Symptoms and Bowel Dysfunction of Patients with the Irritable Bowel Syndrome? A Prospective, Controlled Study with Emphasis on Stool Form. Gut. 1991;32(1):73-9.

25. Lacy BE, Patel NK. Rome Criteria and a Diagnostic Approach to Irritable Bowel Syndrome. J Clin Med. 2017;6(11).

26. Moayyedi P, Andrews CN, MacQueen G, Korownyk C, Marsiglio M, Graff L, et al. Canadian Association of Gastroenterology Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Irritable Bowel Syndrome (Ibs). J Can Assoc Gastroenterol. 2019;2(1):6-29. The Canadian Journal of Diagnosis / March 2025 7

27. Weerts Z, Heinen KGE, Masclee AAM, Quanjel ABA, Winkens B, Vork L, et al. Smart Data Collection for the Assessment of Treatment Effects in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Observational Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020;8(11):e19696.

28. Hetterich L, Stengel A. Psychotherapeutic Interventions in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:286.

29. Burgell RE, Hoey L, Norton K, Fitzpatrick J. Treating Disorders of Brain-Gut Interaction with Multidisciplinary Integrated Care. Moving Towards a New Standard of Care. JGH Open. 2024;8(5):e13072.

30. Black CJ, Thakur ER, Houghton LA, Quigley EMM, Moayyedi P, Ford AC. Efficacy of Psychological Therapies for Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Gut. 2020;69(8):1441-51.

31. Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. Recommendations on Screening for Colorectal Cancer in Primary Care. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2016;188(5):340-8.

32. Leddin DJ, Enns R, Hilsden R, Plourde V, Rabeneck L, Sadowski DC, et al. Canadian Association of Gastroenterology Position Statement on Screening Individuals at Average Risk for Developing Colorectal Cancer: 2010. Can J Gastroenterol. 2010;24(12):705-14.

33. Celiac Canada. Screening and Diagnosis of Celiac Disease. [updated 2023. Available from: https://www.celiac.ca/healthcare-professionals/diagnosis/.

34. Wadhwa A, Al Nahhas MF, Dierkhising RA, Patel R, Kashyap P, Pardi DS, et al. High Risk of Post-Infectious Irritable Bowel Syndrome in Patients with Clostridium Difficile Infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44(6):576-82.

35. Jadallah KA, Nimri LF, Ghanem RA. Protozoan Parasites in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Case-Control Study. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther. 2017;8(4):201-7.

36. Ma C, Congly SE, Novak KL, Belletrutti PJ, Raman M, Woo M, et al. Epidemiologic Burden and Treatment of Chronic Symptomatic Functional Bowel Disorders in the United States: A Nationwide Analysis. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(1):88-98.e4.

37. Nunan D, Cai T, Gardener AD, Ordóñez-Mena JM, Roberts NW, Thomas ET, et al. Physical Activity for Treatment of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;6(6):Cd011497.

38. Johannesson E, Ringström G, Abrahamsson H, Sadik R. Intervention to Increase Physical Activity in Irritable Bowel Syndrome Shows Long-Term Positive Effects. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(2):600-8.

39. Zejnelagic J, Ohlsson B. Chronic Stress and Poor Sleeping Habits Are Associated with Self-Reported Ibs and Poor Psychological Well-Being in the General Population. BMC Res Notes. 2021;14(1):280.

40. Patel A, Hasak S, Cassell B, Ciorba MA, Vivio EE, Kumar M, et al. Effects of Disturbed Sleep on Gastrointestinal and Somatic Pain Symptoms in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44(3):246-58.

41. Orock A, Yuan T, Greenwood-Van Meerveld B. Importance of Non-Pharmacological Approaches for Treating Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Mechanisms and Clinical Relevance. Front Pain Res (Lausanne). 2020;1:609292.

42. Kinsinger SW. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Current Insights. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2017;10:231-7.

43. Goodoory VC, Khasawneh M, Thakur ER, Everitt HA, Gudleski GD, Lackner JM, et al. Effect of Brain-Gut Behavioral Treatments on Abdominal Pain in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology. 2024.

44. Axelsson E, Kern D, Hedman-Lagerlöf E, Lindfors P, Palmgren J, Hesser H, et al. Psychological Treatments for Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Comprehensive Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cogn Behav Ther. 2023:1-20.

45. Lindfors P, Unge P, Arvidsson P, Nyhlin H, Björnsson E, Abrahamsson H, et al. Effects of Gut-Directed Hypnotherapy on Ibs in Different Clinical Settings-Results from Two Randomized, Controlled Trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(2):276-85.

46. Eriksson EM, Andrén KI, Kurlberg GK, Eriksson HT. Aspects of the Non-Pharmacological Treatment of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(40):11439-49.

47. WILSON S, MADDISON T, ROBERTS L, GREENFIELD S, SINGH S, GROUP OBOTBIR. Systematic Review: The Effectiveness of Hypnotherapy in the Management of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2006;24(5):769-80.

48. Noergaard M, Traerup Andersen J, Jimenez-Solem E, Bring Christensen M. Long Term Treatment with Stimulant Laxatives - Clinical Evidence for Effectiveness and Safety? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2019;54(1):27-34.

49. Chapman RW, Stanghellini V, Geraint M, Halphen M. Randomized Clinical Trial: Macrogol/ Peg 3350 Plus Electrolytes for Treatment of Patients with Constipation Associated with Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(9):1508-15.

50. Black CJ, Yuan Y, Selinger CP, Camilleri M, Quigley EMM, Moayyedi P, et al. Efficacy of Soluble Fibre, Antispasmodic Drugs, and Gut-Brain Neuromodulators in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(2):117-31.

51. Chey WD. Symposium Report: An Evidence-Based Approach to Ibs and Cic: Applying New Advances to Daily Practice: A Review of an Adjunct Clinical Symposium of the American College of Gastroenterology Meeting October 16, 2016 • Las Vegas, Nevada. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2017;13(2 Suppl 1):1-16.

52. Chey WD, Shah ED, DuPont HL. Mechanism of Action and Therapeutic Benefit of Rifaximin in Patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Narrative Review. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2020;13:1756284819897531.

53. Pimentel M, Lembo A, Chey WD, Zakko S, Ringel Y, Yu J, et al. Rifaximin Therapy for Patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome without Constipation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(1):22-32.

54. Lembo A, Pimentel M, Rao SS, Schoenfeld P, Cash B, Weinstock LB, et al. Repeat Treatment with Rifaximin Is Safe and Effective in Patients with Diarrhea-Predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2016;151(6):1113-21.

55. Zaxine (Rifaximin) [Product Monograph]. Bridgewater, Nj: Salix Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2018.

56. Özdener AE, Rivkin A. Eluxadoline in the Treatment of Diarrhea-Predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2017;11:2827-40.

57. Lembo AJ, Lacy BE, Zuckerman MJ, Schey R, Dove LS, Andrae DA, et al. Eluxadoline for Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Diarrhea. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;374(3):242-53.

58. Viberzi (Eluxadoline) [Product Monograph]. Markham, On: Allergan Pharma Co., 2018.

59. Kamuda JA, Mazzola N. Plecanatide (Trulance) for Chronic Idiopathic Constipation and Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Constipation. P t. 2018;43(4):207-32.

60. Jacobs JW, Leadbetter MR, Bell N, Koo-McCoy S, Carreras CW, He L, et al. Discovery of Tenapanor: A First-in-Class Minimally Systemic Inhibitor of Intestinal Na+/H+ Exchanger Isoform 3. ACS Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2022;13(7):1043-51.

61. Chey WD, Lembo AJ, Lavins BJ, Shiff SJ, Kurtz CB, Currie MG, et al. Linaclotide for Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Constipation: A 26-Week, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial to Evaluate Efficacy and Safety. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(11):1702-12.

62. Nee JW, Johnston JM, Shea EP, Walls CE, Tripp K, Shiff S, et al. Safety and Tolerability of Linaclotide for the Treatment of Chronic Idiopathic Constipation and Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Constipation: Pooled Phase 3 Analysis. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;13(4):397-406.

63. Constella (Linaclotide) [Product Monograph]. St-Laurent, Qc: Abbvie Corporation, 2022.

64. Brenner DM, Fogel R, Dorn SD, Krause R, Eng P, Kirshoff R, et al. Efficacy, Safety, and Tolerability of Plecanatide in Patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Constipation: Results of Two Phase 3 Randomized Clinical Trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(5):735-45.

65. Barish CF, Crozier RA, Griffin PH. Long-Term Treatment with Plecanatide Was Safe and Tolerable in Patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Constipation. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35(1):81-5.

66. Trulance (Plecanatide) [Product Monograph]. Laval, Qc: Bausch Health, Canada Inc., 2021.

67. Chey WD, Lembo AJ, Rosenbaum DP. Efficacy of Tenapanor in Treating Patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Constipation: A 12-Week, Placebo-Controlled Phase 3 Trial (T3mpo-1). Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115(2):281-93.

68. Chey WD, Lembo AJ, Yang Y, Rosenbaum DP. Efficacy of Tenapanor in Treating Patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Constipation: A 26-Week, Placebo-Controlled Phase 3 Trial (T3mpo-2). Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116(6):1294-303.

69. Lembo AJ, Friedenberg KA, Fogel RP, Edelstein S, Zhao S, Yang Y, et al. Long-Term Safety of Tenapanor in Patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Constipation in the T3mpo-3 Study. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2023;35(11):e14658.

70. Isbrela (Tenapanor) [Product Monograph]. Montreal, Qc: Knight Therapeutics Inc., 2023.

71. Black CJ, Burr NE, Quigley EMM, Moayyedi P, Houghton LA, Ford AC. Efficacy of Secretagogues in Patients with Irritable Bowel syndrome with Constipation: Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(6):1753-63.

72. Black CJ, Burr NE, Camilleri M, Earnest DL, Quigley EM, Moayyedi P, et al. Efficacy of Pharmacological Therapies in Patients with Ibs with Diarrhoea or Mixed Stool Pattern: Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Gut. 2020;69(1):74-82.

73. Nelson AD, Black CJ, Houghton LA, Lugo-Fagundo NS, Lacy BE, Ford AC. Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis: Efficacy of Licensed Drugs for Abdominal Bloating in Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2021;54(2):98-108.

74. Thompson WG, Heaton KW, Smyth GT, Smyth C. Irritable Bowel Syndrome in General Practice: Prevalence, Characteristics, and Referral. Gut. 2000;46(1):78-82.

75. Halpert A. Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Patient-Provider Interaction and Patient Education. J Clin Med. 2018;7(1).

76. Fritsch P, Kolber MR, Korownyk C. Antidepressants for Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Can Fam Physician. 2020;66(4):265.

77. Hackett C, Kolber MR. Low Fodmap Diet. Can Fam Physician. 2015;61(8):691.

78. Wilkins T, Pepitone C, Alex B, Schade RR. Diagnosis and Management of Ibs in Adults. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86(5):419-26.

79. Wilkinson JM, Gill MC. Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Questions and Answers for Effective Care. Am Fam Physician. 2021;103(12):727-36.