The diagnosis and classification of chronic insomnia has undergone some changes to increase clarity in recent years. The American Academy of Sleep Medicine’s International Classification of Sleep Disorders1 defines insomnia disorder as “a complaint of trouble initiating or maintaining sleep which is associated with daytime consequences and is not attributable to environmental circumstances or inadequate opportunity to sleep.”1 Insomnia disorder is classified as chronic if the problems occur at least three times per week and persist for at least three months.1 This is similar to how DSM-V categorizes insomnia disorder, although these criterion may be more clinically relevant as they indicate that both comorbidity (other sleep disorders, mental or medical comorbidity) and a time course should be specified (episodic, persistent and recurrent).2 Short-term insomnia disorder (ICSD-3) or other specified insomnia disorder in DSM-V can be diagnosed when the sleep problems meet the above symptom criteria, but have not lasted three months.1 Short-term (or acute) and chronic insomnia may be different ends of an overlapping spectrum, and may ultimately lead to different treatment modalities.3 In Canada, one study showed that about 40% experienced insomnia symptoms, and 13% have insomnia disorder.4 In another study, 86% of these patients met criteria at 12 months, indicating a high burden of insomnia disorder that is chronic.5

RISK FACTORS

There are certain populations of individuals who are at increased risk of insomnia disorder: Older age, female sex, and comorbid medical or psychiatric conditions are the most important risk factors.4-7 There should be a higher index of suspicion for insomnia disorder in individuals with these characteristics. A focused, personal history may also reveal longstanding social and environmental factors that may be contributing factors (e.g., trauma, work or family difficulties).4,8

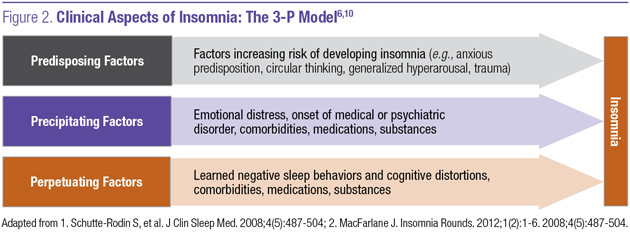

An algorithm depicting the recommended assessment of a patient with symptoms of insomnia is shown in Figure 1.9 A layered approach taking into account predisposing, precipitating and perpetuating factors is often helpful as well (Figure 2).6,10

IMPACT OF COMORBIDITIES

There are many comorbidities linked with chronic insomnia, and common ones to screen for include sleep apnea, depression, anxiety and pain disorders;9 Other health conditions (e.g., bipolar disorder, ADHD, menopause) may also be considered if there is a reasonable suspicion of these disorders.9 The prevalence of insomnia in psychiatric conditions such as anxiety, depression, substance abuse, and others can be fairly high, ranging from 32 to 93%.12 The use of some combination of standardized questionnaires for insomnia (i.e., the Insomnia Severity Index) and potential major comorbidities is often useful.6,13 Reviewing substances, and over-the-counter and prescription medications is also critical. This approach is outlined in Table 1.

Assessing the presence and status of comorbidities at the time of diagnosis is critical, to help differentiate whether the initial treatment plan will focus on the chronic insomnia, the comorbidity or both in conjunction.9 For example, if sleep apnea, mood, anxiety or pain are major concerns, optimization of these concerns may take precedence in addition to treatment strategies for chronic insomnia. Also, a lack of improvement in chronic insomnia through standard treatments should alert the clinician that other comorbidities may be present. Certain off-label agents may also be helpful if the patient has insomnia in addition to another significant comorbid condition for which that medication has evidence.9 If improvement in the comorbidity is not commensurate with sleep improvement or vice versa, the diagnosis and treatment plan may need to be revised.

ASSESSING SLEEP HEALTH

Realistic optimization of sleep behaviors and environmental factors that can affect sleep are a foundational component of comprehensive insomnia management, and this should begin from the time a patient is diagnosed. Even if formal cognitive behavioral therapy is not pursued or unsuccessful, a cognitive behavioral approach to chronic insomnia is necessary, whether pharmacotherapy is instituted or not. An analogy could be making dietary changes as a foundation of the treatment of diabetes. Overall, the diagnosis of chronic insomnia is an evolving process involving a dynamic interplay between a patient’s sleep, cognitive and behavioral factors as well as contributing comorbidities. It requires ongoing follow up to set the stage for successful treatments in the right order to maximize the chance of success in management.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

A layered approach looking at predisposing, precipitating and perpetuating factors is often helpful in the diagnosis of chronic insomnia.

Screening and ongoing awareness of comorbid conditions, contributing medications and substances are necessary in chronic insomnia diagnosis.

A cognitive behavioral approach and consistent follow up are necessary to set the stage for successful treatment in chronic insomnia.

References:

1. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders. 3rd ed. Darien, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2014.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th, ed. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

3. Perogamvros L, Castelnovo A, Samson D, et al. Failure of fear extinction in insomnia: An evolutionary perspective. Sleep Med Rev; 2020 June.

4. Morin CM, LeBlanc M, Bélanger L, et al. Prevalence of insomnia and its teatment in Canada. Can J Psychiatry; 2011; 56(9):540-8.

5. Morin CM, Bélanger L, LeBlanc M, et al. The Natural History of Insomnia: A Population-Based 3-Year Longitudinal Study. Arch Intern Med. 2009; 169(5):447–453.

6. Schutte-Rodin S, Brooch L, Buysse D, et al. Clinical guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic insomnia in adults. J Clin Sleep Med; 2008; 4(5):487-504.

7. Finan PH, Smith MT. The comorbidity of insomnia, chronic pain, and depression: dopamine as a putative mechanism. Sleep Med Rev; 2013; 17(3):173-83.

8. Calem M, Bisla J, Begum A, et al. Increased prevalence of insomnia and changes in hypnotics use in England over 15 years: analysis of the 1993, 2000, and 2007 National Psychiatric Morbidity Surveys. Sleep; 2012; 35(3):377–84.

9. Alberta Guidelines. 2015, Towards Optimized Practice, Assessment to Management of Adult Insomnia - Clinical Practice Guidelines. December 2015.

10. MacFarlane. Taking Control of Acute Insomnia – Restoring Healthy Sleep Pattens. Insomnia Rounds. 2012; 1(2):1-6.

11. Calem M, Bisla J, Begum A, et al. Increased prevalence of insomnia and changes in hypnotics use in England over 15 years: analysis of the 1993, 2000, and 2007 National Psychiatric Morbidity Surveys. Sleep 2012; 35(3):377–84.

12. Geiger-Brown JM, Rogers VE, Liu W, Ludeman EM, Downton KD, Diaz-Abad M. Cognitive behavioral therapy in persons with comorbid insomnia: A meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2015 Oct; 23:54-67.

13. McCrae CS, Lichstein KL, Secondary insomnia: diagnostic challenges and intervention opportunities. Sleep Med Rev. 2001; 5:47-61.

Development of this article was made possible through the financial support of EISAI Ltd. The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of EISAI Ltd. The author had complete editorial independence in the development of this article and is responsible for its accuracy. The sponsor exerted no influence in the selection of content or material published.